Stephen Hawking may have believed “There is no God. No one directs the universe.” But the jury still appears to be out for much of the rest of the global scientific community, according to research by Brandon Vaidyanathan, associate professor and chair of sociology at The Catholic University of America, and his co-authors of Secularity and Science: What Scientists Around the World Really Think About Religion (Oxford University Press, 2019).

“There’s a common myth — largely a creation of the West — about science and religion being in conflict, but it appears that most scientists really are not hostile to religion,” says Vaidyanathan. “In fact, on a global scale, we found that a significant portion of scientists can be characterized as having religious identities, practices or beliefs, and nontrivial proportions say they have ‘no doubt’ that God exists.”

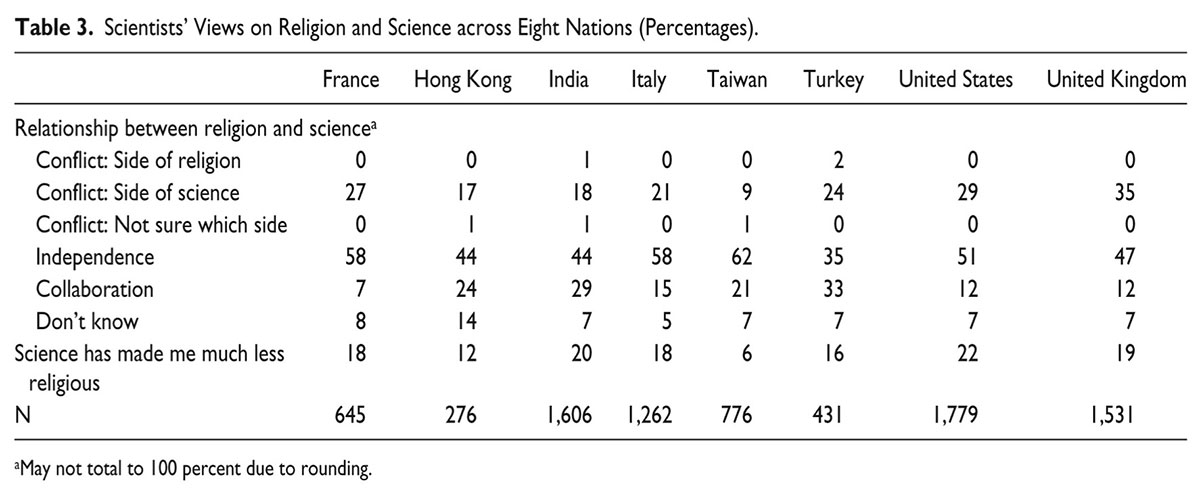

Hawking, the late theoretical physicist, makes the “There is no God” pronouncement in his final, just-released book, Brief Answers to the Big Questions. However, of the nearly 10,000 physicists and biologists in eight countries recently surveyed for Secularity and Science, fewer than one in four view religion and science as being directly in conflict. Hawking’s home, the United Kingdom, had the highest share of scientists who believe the two are in conflict, 35 percent, while only 9 percent of scientists in Taiwan feel that way. In the United States, just 29 percent of scientists surveyed believe science and religion are in conflict.

Much larger segments of the scientists polled (more than half in four countries — France, Italy, Taiwan and the U.S.) see science and religion as independent of each other. And appreciable minorities — up to roughly a third in India and Turkey — see science and religion as compatible, with many believing that faith can even inspire scientific pursuit.

Vaidyanathan says it is important to understand what scientists in different national and cultural contexts think about the religion-science interface, because in most countries, religion can influence the transmission and public acceptance of science across a broad range of issues, from the teaching of evolution (or creationism) in public schools, to climate change, and embryonic stem cell research.

Meanwhile, Elaine Howard Ecklund, the Herbert S. Autrey Chair in Social Sciences at Rice University and principal investigator on the 2011-16 Religion Among Scientists in International Context, or RASIC, survey at the heart of Secularity and Science, is concerned that because of his notoriety in popular culture, Hawking’s pronouncement may create a false impression about the religious beliefs shared by a large number of scientists.

“Stephen Hawking left a great scientific legacy. I do not think it is the intent of this recent work, but it is dangerous for science if Hawking's religious legacy is to leave the public with the impression that scientists are all against God or, worse yet, against religious people,” says Ecklund, founding director of Rice’s Religion and Public Life Program. “Unfortunately, this seems to be how some media sources and pundits are framing his recent book.”