By Katie Bahr

Illustrations by LA Johnson

Inside the headquarters of the Central Intelligence Agency, there’s a display of spycraft tools dating back to the earliest days of the organization’s history. Messages written in invisible ink. A radio transmitter hidden in a martini olive. A smoking pipe communicator that uses bone conduction technology. And cameras hidden in brooches, in cigarette packs, in umbrellas, and even in other cameras.

Inside the headquarters of the Central Intelligence Agency, there’s a display of spycraft tools dating back to the earliest days of the organization’s history. Messages written in invisible ink. A radio transmitter hidden in a martini olive. A smoking pipe communicator that uses bone conduction technology. And cameras hidden in brooches, in cigarette packs, in umbrellas, and even in other cameras.

The CIA museum collection tells the story of how the world of intelligence has changed over the decades, progressing from hidden cameras to modern satellites and cybertech. One of the most recent exhibits is a scale model of the Abbottabad compound where Navy SEALs working in conjunction with the CIA conducted the mission that killed Osama bin Laden. Hanging on the wall beside the model is a Russian-made AK-47 believed to have belonged to bin Laden himself.

The artifacts in the museum are compelling, like objects from a movie. But cinematic glamour can’t compare to the reality these artifacts represent. As part of a field trip to the agency’s headquarters in Langley, Va., this spring, 16 Catholic University students stopped first at the CIA’s Memorial Wall. There, they could see a book where fallen officers are commemorated with their names or — if their identities are still classified — a single star.

“There are certain pieces at the CIA that are just, ‘Wow,’” says senior politics major Ben Hewitt. “It’s such a powerful place and there are so many things to learn.”

Hewitt is the cofounder of the University’s Intelligence Club, which organizes regular trips to intelligence organizations around the Washington, D.C., area, including the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, the National Security Agency, and the National Reconnaissance Office. Hewitt planned the CIA visit with the support of the University’s Intelligence Studies Program, which offers an interdisciplinary certificate program for students interested in gaining a deeper understanding of the mysterious world of intelligence. The program is led by Nicholas Dujmovic, a retired CIA officer and clinical assistant professor of politics, who uses his connections in the field to provide students with unique experiences like the CIA excursion.

As part of this year’s CIA field trip, Hewitt and other students received a private tour of the museum, as well as briefings on the organization’s history, its mission, and current programs. In one briefing, CIA staff historian Randy Burkett walked students through a hypothetical exercise depicting how CIA officers in various roles work together to recruit people from other countries to act as spies for America, taking into consideration the many factors that motivate someone to spy, including financial rewards, the pursuit of excitement, or ideology. One of the most important skills a CIA officer can have, he says, is the ability to build deep relationships and trust with these agents.

“Spying on one’s country is not a logical act. It can be very risky,” Burkett says. “People don’t decide to spy from the head, but from the heart. Oftentimes, the essence of the job of an operations officer is to start a conversation to convince them. You’re hoping to build a relationship where they feel they can come to you with any problem they have, where they will be listened to and understood, and then you can move them toward the big ideas.”

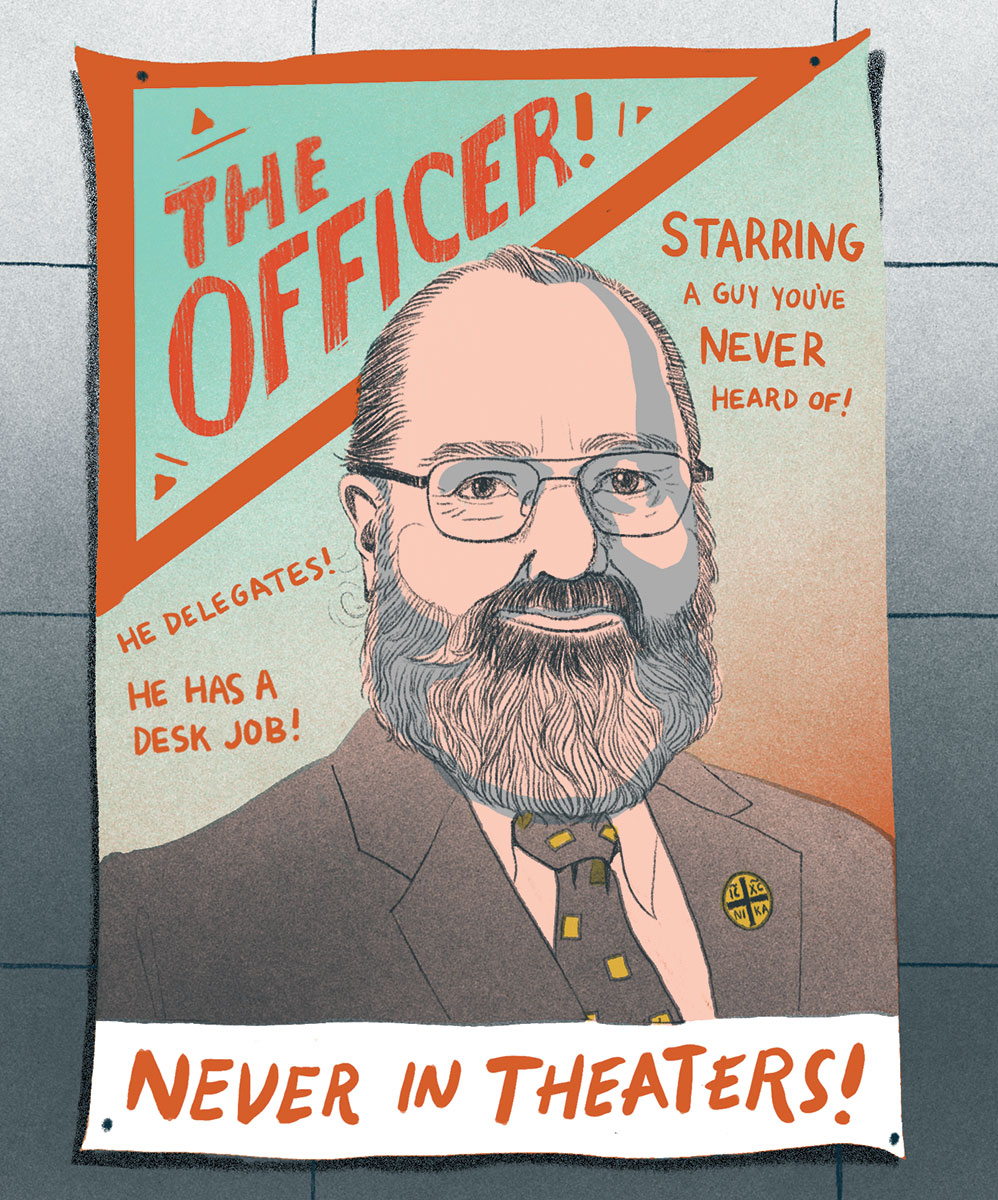

While pop culture representations of intelligence seem thrilling and dramatic, Burkett says they are not usually accurate. In real life, CIA officers don’t carry weapons, kill people, or coerce with blackmail or sexual manipulation. More commonly, officers have desk jobs where they are researching in classified databases, writing reports and assessments, or coordinating the work of others.

Separating fantasy from reality is important to Dujmovic. He wants to teach students about what intelligence organizations actually do, and why their work is valuable. In reality, he says, car chases, the use of weapons, and other dramatic actions are very rare.

“The attraction of working in intelligence is that there is a mystique to it, but it is not really how it is portrayed in movies and television,” says Dujmovic. “In actuality, intelligence is really important, it’s a way to serve your country, and it’s a very interesting job. You’re doing important work that matters, that contributes to something greater than yourself.”

Before coming to Catholic University in 2016, Dujmovic worked at the CIA for 26 years in a number of positions. For him, the road started in the Coast Guard, where he was assigned to pursue graduate studies to teach at the Coast Guard Academy. While in grad school, Dujmovic took his first intelligence course and was immediately intrigued. Then, around the time he was wrapping up his 10 years of military service, he learned the CIA was hiring.

Dujmovic was hired as an analyst, thanks to his military background, his Russian language skills, and his writing ability. After that, he had posts in the State Department, the Pentagon, and at a U.S. embassy in central Europe. He worked as a speechwriter for Deputy Director George Tenet and, from 1997 to 2000, he was on the staff that produced the President’s Daily Brief, a top-secret document that updates the president on national security issues. While working as a manager in the Southeast Asia division, Dujmovic delivered briefs to Capitol Hill. His last position with the agency, which he held for 11 years, was working as a CIA historian.

“I still think that’s one of the best jobs in the world, working with history like that,” Dujmovic says. “It was just trying to learn as much as you could about CIA history. It was always something different and something new.”

When he was approached by then-Provost Andrew Abela about starting the Intelligence Studies Program at Catholic University, Dujmovic liked the idea of sharing his love for the field with a new generation of students. “It’s a way to give back,” Dujmovic says. “I tell people up front that this program has a vocational edge to it. I’m not a recruiter, but I know what it takes to get into the CIA, so I can help.”

In setting up the program, Dujmovic knew he wanted to provide students with an in-depth understanding of intelligence topics like collection, analysis, covert action, and accountability. Students are required to take three politics courses and three electives, including at least one from outside the politics department, covering a range of subjects from cryptography (solving codes) and steganography (concealing messages within other messages) to surveillance, border control, and the psychology of terrorism.

Dujmovic plans numerous lectures and events each year, inviting friends from the intelligence field such as Michael Hayden, a retired U.S. Air Force four-star general and former director of the National Security Agency, principal deputy director of National Intelligence, and director of the CIA. In March, Dujmovic coordinated with the University’s Institute for Human Ecology to host “The Humanity of Espionage,” a panel discussion in which four former CIA spy handlers discussed how human dignity can play a role in a life of intelligence collection.

John Liddi has taught courses on terrorism, border control, and surveillance as part of the program. Prior to teaching at the University, he worked at the FBI as an agent for 30 years. He praises the program for the way it shines a light on the field. “It really opens the eyes of students to what intelligence work is really like, what its purpose is, and how essential it is to national security,” he says. According to Liddi, several graduates have gone on to work at the FBI or other intelligence organizations.

If nothing else, Dujmovic says, he wants to give students an honest perspective on the intelligence field. He wants them to appreciate how challenging the work can be, and why it is important.

“I’m trying to give the correct impressions, warts and all,” he says. “I’m not trying to propagandize or be a shill for the intelligence community, and there are times I’m highly critical. It’s a fallen world with fallen humans in it and nobody is immune from that.”

Learning about intelligence in D.C. has been a perfect opportunity for Hewitt. Since he was little, he has been interested in serving his country.

“I was obsessed with [the TV show] The West Wing and I wanted to work at the White House, or on the Hill,” he says. “I even dressed up as the president in fifth grade, with a button that said ‘Hewitt 2020.’ It was really something that was always in my head, that I wanted to do good.”

Compared to the many spy-themed movies and TV shows he has seen, Hewitt says the University’s program has “made it easy to understand that what officers are doing is not some dark thing. They don’t have as much money or resources as what’s seen in the movies, so they have to be strategic about what they do and how they conduct their work.”

Hewitt found himself drawn to the security aspect of the work. He liked the idea that he could work as a civil servant while also protecting the lives of American people. During the summer before his junior year, he interned with the Federal Aviation Administration, which monitors information affecting the National Airspace System and related industries.

“Working in that kind of national security job, it makes me feel like I have a meaning behind what I do, like I can go to bed at night and think, ‘I did something good,’” he says.

Currently, Hewitt is focusing on world politics with a minor in Islamic studies. His favorite aspect of the Intelligence Studies Program has been meeting people working in the field and hearing about what their jobs actually entail. Now, Hewitt says, when some of the intelligence professionals come to campus, “they know me by name.”

One of the things Hewitt remembers about his CIA visits is the Bible verse etched in the wall of the main lobby entrance: “And ye shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free” (John 8:32).

One of the things Hewitt remembers about his CIA visits is the Bible verse etched in the wall of the main lobby entrance: “And ye shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free” (John 8:32).

The idea of having a biblical passage in an organization such as the CIA is an interesting one, Hewitt says, because the work of the organization can be morally complicated. For him, it all comes down to ethics.

“It is an interesting argument to say you can be a Christian and an intelligence officer,” he says. “But you’re always working and doing what’s best for your country.”

In recent years, the world of intelligence has often been criticized by the news media and politicians, especially President Donald Trump. Because the coverage has not always been positive, Dujmovic believes it is more important than ever for students to learn about what intelligence is.

“This is an interesting time because intelligence seems to be in the spotlight both for good and for bad reasons,” he says. “It’s no secret that some in the field are concerned about the statements the president has made because it affects people when you have these statements and tweets. It makes the job a little harder.”

One important aspect of intelligence that always remains, Dujmovic says, is its standard of objectivity. Despite anything happening in the political landscape, intelligence officials are called to discern the truth about what is happening nationally and around the world.

“Intelligence professionals must always be self-aware and reflect on, ‘Am I giving the unvarnished perspective and the truth as we see it, or have I been influenced by politics, pressures, or expectations to shade that analysis?’” says Dujmovic. “Ultimately, we all swear an oath to the constitution and the people of the country and not to any particular administration.”

Hewitt thinks the current political climate puts even more responsibility on intelligence officials to remain objective and honest at all times. He’s inspired by their resilience when, sometimes under great pressure, they share information policy makers might not want to hear.

“It makes me want to work in the field more because I want to be able to do that,” he says. “At the end of the day, they’re doing a lot of good work to help America and they’re not giving up.”

The truth-seeking aspect of intelligence also interests senior Cara DiMarcantonio, a politics major pursuing the Intelligence Studies certificate.

“The thing I love about intelligence is that it’s apolitical, and it’s concerned with gaining a sense of truth,” she says. “It’s not about trying to prove that, ‘I’m right and you’re wrong,’ it’s just trying to share the truth. I think that’s extremely important in today’s climate.”

While growing up, DiMarcantonio developed a passion for justice and protecting others thanks to the example of her grandfather, a police officer. From her classes with Dujmovic and her experiences with the Intelligence Club, she says she has learned how the world of intelligence can serve as an extension of her Catholic faith, allowing her to help people and build relationships.

“That’s what is always important, being able to connect with other people and to learn from them,” she says. “Strong relationships make the world a safer place.”