Earning a degree late in life was just one component of a life transformation for a recovering addict. Now he can’t get enough of helping others.

By Ellen N. Woods

By Ellen N. Woods

This story appeared in the Winter 2018 issue of CatholicU Magazine.

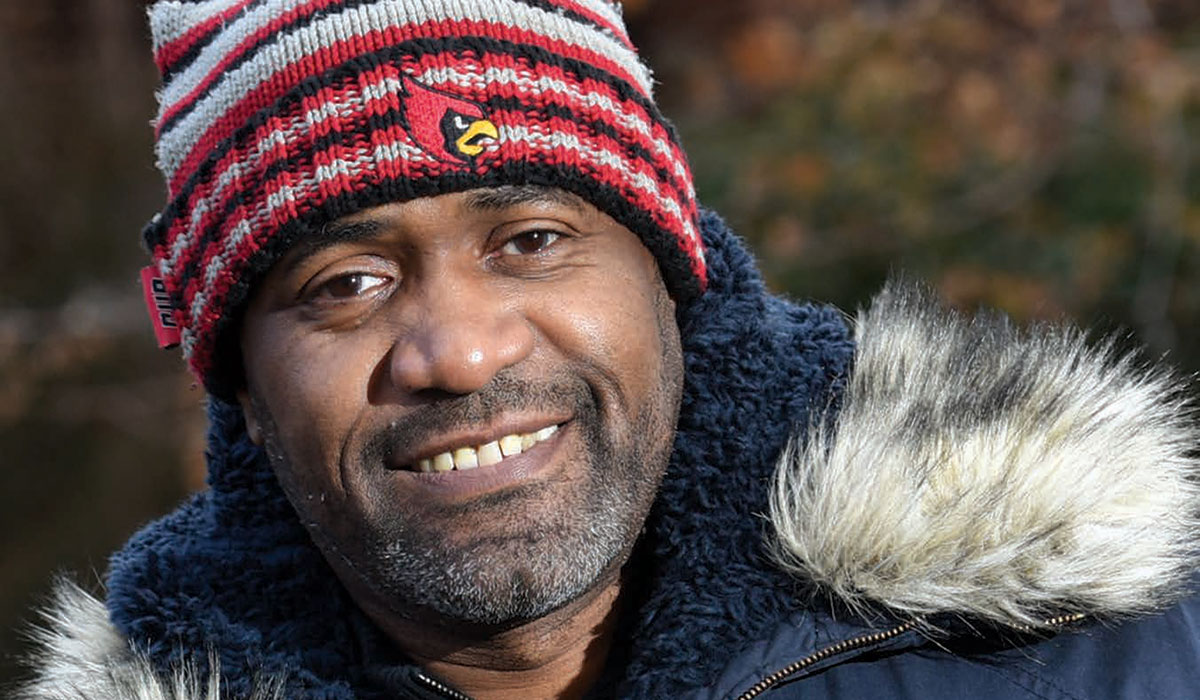

Kenny Baldwin flashes his signature smile as he walks through the Northwest Washington, D.C., neighborhood where he was raised. A shop owner gives him a wave. He gets a hug from an elderly resident who knew him as a little boy growing up on Longfellow Street.

Baldwin doesn’t live in the Brightwood neighborhood anymore, but he likes to come back from time to time. Sometimes he heads to the street corner where the guys hang out — some of them he knows, others he doesn’t. He’s not there to lecture. He simply wants to be an example; to offer hope. “I just want them to see there are other options,” he says.

More than a decade ago, Baldwin was a fixture on the corner of Kennedy and First — buying, selling, and using drugs. He points to a house up the hill. “There was a triple homicide there. I knew the people who were killed and I knew the people who killed them.” He walks past an alley where he once eluded police officers chasing him after a drug-fueled armed robbery. “I ditched the gun right there,” he says.

Cocaine was my go-to. It had a power over me, like I was being held captive. There were moments where the window opened and I caught an occasional breeze. I wanted to stop. And just like that the breeze was gone and I was back in that stifling room. The drug was calling my name.

On January 16, Baldwin celebrated 10 years of sobriety. Staying clean was not his only accomplishment of the last decade. The 50-year-old earned an associate’s degree and a bachelor’s degree from Catholic University’s Metropolitan School of Professional Studies (MSPS). He completed the Catholic Charities Professional Counseling Education Program and became a certified addiction counselor. He has been steadily employed helping individuals who are dealing with addiction and other challenges such as homelessness, domestic violence, and mental illness. He is currently a mental health counselor for a federal government agency in Washington, D.C., that serves offenders on parole and probation. His volunteer work with “returning citizens” (the increasingly preferred term for ex-offenders) has been honored with three separate awards from the White House: the President’s Volunteer Service Award, the Unsung Hero Award, and the Honor Drum Major Award. Each one, he proudly says, came with a signed letter from President Barack Obama.

Baldwin’s 27 years of addiction began at age 13. He wanted an escape from the domestic violence taking place in his home. Drugs were readily available in his neighborhood and they allowed him to gain acceptance with a group of peers.

He managed to graduate from high school while using drugs. He entered the University of the District of Columbia (UDC), got a government job, and became a father. By his early 20s, his drug addiction had cost him his chance at a college education, his job, his marriage, and his relationship with his two little boys. He turned to criminal activity to support his habit.

The worst thing about prison is all the concrete and steel. The bars on your cell, your bed, the walls, the floor. You long for something green. Every time I was released, I couldn’t wait to see a tree.

Baldwin and his mother. "I turned away early on as a teen from the values she taught me."

Baldwin and his mother. "I turned away early on as a teen from the values she taught me."During his years of addiction, Baldwin was arrested upwards of 80 times, spending a total of 14 years incarcerated. Along the way, his mother, who eventually left her abusive husband, was an unwitting enabler. She was a safety net for her son, taking him in when he relapsed or was released from jail. But by late 2007 she had had enough. She closed her door to her son and told her extended family to do the same. “That total amputation from my family was my defining moment,” says Baldwin.

When Baldwin entered rehab in January 2008, it was his fifth try at getting clean. “This time it was different, and I immediately knew I wanted to dedicate the rest of my life to helping others,” he says.

When he completed his rehab program, he made the critical decision to move to a transitional sober living home. This kind of accountability was something he had never tried before, and it was enough to show his mom, who was battling Parkinson’s disease, that he meant business this time. A little more than a year into his sobriety, Baldwin moved into an apartment. His mom furnished it for him. “That was her way of showing support,” says Baldwin. His mother died a month later. For Baldwin there was some comfort in knowing she had enjoyed more than a year with her newly sober son.

Some days when I think about those 27 years I’m sad. I have so much regret, especially toward the people I hurt. But there are just as many days, I feel gratitude. Without that life experience, I’m not sure I’d be in this place right now offering hope to others.

Every day for the last 10 years, I’ve made a conscious decision not to use drugs. There have been so many days I could have used again. My mom died, and not long after that I lost my dad and my grandfather. A close friend died of a heroin overdose. I had a broken engagement. Even just a dreary day. It would be so easy to go buy two bags. But I know what the end result would be. Maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, eventually I would end up in handcuffs.

With a criminal record, his job options were limited. Through contacts at his rehab program he was referred to Catholic Charities, where he was hired as a residential counselor, working at night overseeing residents who were struggling with addiction, homelessness, and criminal offenses. During the day he worked as a mentor for adjudicated youth through Serenity Inc, a social services agency. He was putting in about 60 hours a week between the two jobs.

While at Catholic Charities, he met Nancy Butler, the director of Catholic Charities Institute, who encouraged him to enroll in the Professional Counseling Education Program.

I found that helping others is empowering. I found I had a purpose and that was a new experience for me. A really good day is when someone tells me, ‘Your story touched me and helped me through one more day of recovery.’ The very best day is when I can help someone reconnect with family and begin to mend broken relationships.

Baldwin had a goal. He wanted to become a certified addiction counselor. But in addition to the program at Catholic Charities, he would need an associate’s degree. Butler had developed an alliance with MSPS that allowed her to refer qualified students who had completed her counseling program to enroll in the MSPS associate’s degree program in human service administration with scholarship assistance.

Once he got a taste for education, Baldwin wanted to keep going. He was accepted into the MSPS Bachelor of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies focusing on human services administration. He says that balancing full-time work with evening classes was challenging. In some courses, like Social Problems and Case Management and Crisis Intervention, he brought his personal experience to classroom discussion, which he says was confidence building. He graduated cum laude and was inducted into the Alpha Sigma Lambda Honor Society.

“Kenny is intelligent, charismatic, full of joy, and gentle,” says William Buracker, associate dean at MSPS (pictured above with Baldwin). “He had an incredible ability to relate his struggles and his strengths to what he was learning in the classroom, and to share those experiences with his classmates in a way that helped them succeed. Our students are really good at that. They lift each other up.”

I wore a cap and gown for both degrees. I celebrated with everyone at MSPS. The school is a family. Everything they do there is geared to helping adult learners, people like myself who have a life story and are trying to better themselves. It took me 31 years to get my bachelor’s degree, and I don’t want to stop there.

Last fall, Baldwin began working toward a master’s degree in clinical rehabilitation counseling and mental health counseling at UDC. His plan is to become a Licensed Professional Counselor. As he advances his education, Baldwin says he wants to continue to help those in recovery one-on-one. He also wants to change attitudes.

We need to stop viewing addicts in a negative light — ‘Junkies.’ ‘Crackheads.’ Things like that. That only perpetuates further drug use. Sure we are getting better recovery programs. But beyond that we need a paradigm shift. Drug addiction is a disease. And for those suffering with the disease, we need to tell them they matter, that they have value, and they have something to offer society.