Jacco Dieleman, a research associate professor in the Department of Semitic and Egyptian Languages, recently made a startling discovery while examining artifacts housed within Catholic University’s Semitics/ICOR collections. Thanks to his years of research in the field of Egyptology, Dieleman was able to identify a papyrus fragment from the University’s collection as a small piece of a larger papyrus scroll from the so-called Tebtunis Temple Library, an important collection of ancient manuscripts that is beginning to shed new light on the world of Ancient Egypt.

The Tebtunis Temple Library, which was excavated in the town of Tebtunis in Egypt in the early 20th century, contains numerous papyri written in the Demotic Egyptian and Koine Greek languages, dating back to the second century A.D. Among the many documents found in the collection are texts about rituals, medical practices, and works of literature. The largest parts of the library collection are housed today in Copenhagen at the Carlsberg Papyrus Collection, but additional pieces of papyri manuscripts are scattered around the world.

According to Dieleman, the fragment found at Catholic University is part of a scroll inscribed with a story about the Egyptian Prince Inaros, who rebelled against the Assyrian occupiers around 665 B.C. After his death, Inaros became an Egyptian folk hero comparable to King Arthur, with many fictional tales written about his heroism for centuries to come.

Dieleman first became aware of the possibility that a papyrus fragment could be in the area thanks to his colleague Professor Kim Ryholt of the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, who sent him a 30-year-old Xerox copy of the fragment piece. Relying on the Xerox copy, Ryholt had recently identified the piece as joining similar fragments in Reykjavik, Iceland, and Berlin. The Xerox did not say where the fragment was held, but Ryholt had been told that it might be in the D.C. area. Later, when Dieleman was examining Catholic University’s collection, he recognized the fragment immediately.

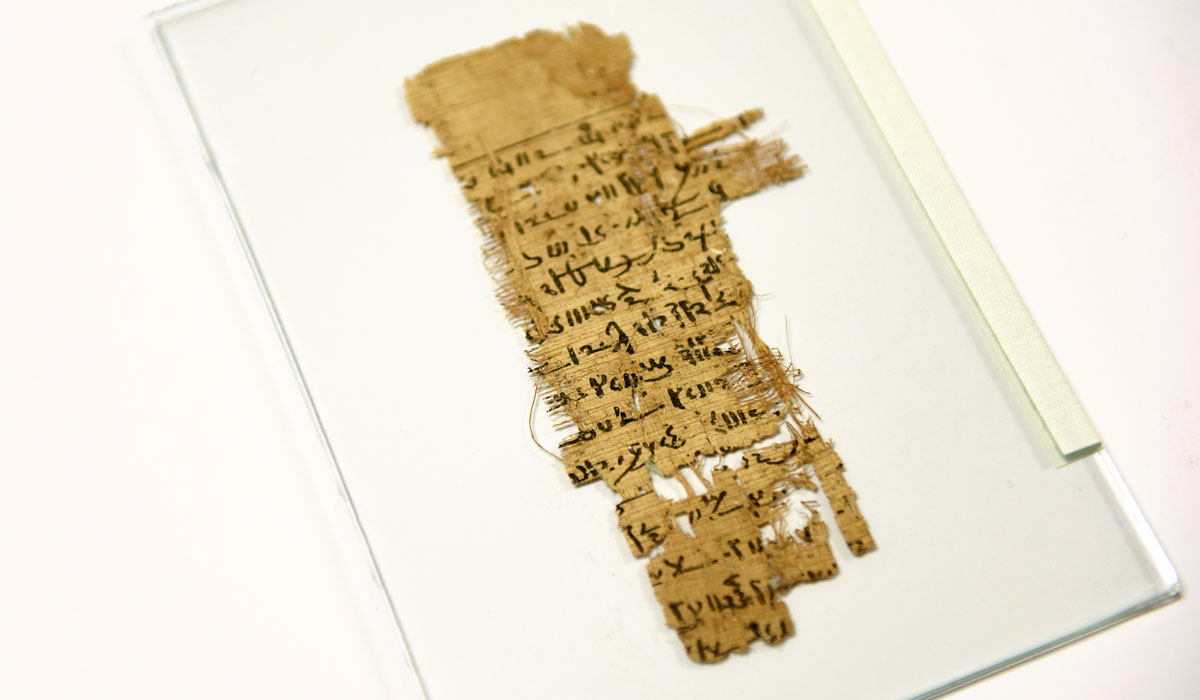

“I wrote to him and said, ‘I think you may recognize this piece,’” Dieleman said. While the fragment itself is only a few inches long, it is inscribed in the same Demotic Egyptian language used in the other pieces of the manuscript. It also includes the name of a major character from the Inaros stories. As it joins directly to the fragment in Reykjavik, scholars can now reconstitute and read a broken column of text.

“What’s interesting about the story cycle is that it includes all these stories about a glorious past of Egypt right at the time when Egypt was ruled by first Greek and then Roman overrulers,” Dieleman said. It’s likely, he theorizes, that the ancient Egyptians looked to the Inaros stories as a form of nostalgic escapism during a difficult political period.

How the piece ended up at Catholic University is another mystery, Dieleman noted. At the time of the Tebtunis Library’s excavation, many papyri pieces were sold on the antiquities market and scattered around the world, with the largest chunks being purchased by collectors in Copenhagen and Florence. The University’s fragment pieces were archived as part of the Henri Hyvernat Collection, named for a founding professor at the University who amassed a large collection of artifacts related to the Middle East in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

To find a piece of papyrus fragment from the Tebtunis Library at Catholic University was a great surprise to Dieleman. As more and more Egyptologists have begun to study the Tebtunis documents, Dieleman believes the Tebtunis Temple Library will rise to the same level of importance as the Dead Sea Scrolls.

“This little piece of papyrus, insignificant at first sight, is actually an important part of an ancient puzzle which shows what Ancient Egyptians were reading and studying,” Dieleman said. “This research is slowly revolutionizing Egyptology from within and hopefully one day will change the way we think about how Ancient Egyptians collected and disseminated knowledge.”