In March, Paul Rahn’s field placement at Miriam’s Kitchen, a homeless service organization in Washington, D.C., was cancelled due to the COVID-19 crisis. The good news for Rahn, who is in his foundation year of Catholic University’s master’s in social work program, was that he had already met the required number of field placement hours. In a profession that requires licensure, and therefore has strict requirements for student fieldwork hours, this was a bit of a silver lining.

But Rahn’s desire to serve vulnerable populations didn’t go away with the end of his formal field placement. Amid a worsening health crisis, it only deepened.

At Miriam’s Kitchen, Rahn had been involved in case management. “I spent a lot of time in the dining room, getting to know our clients,” he says, “so that I could assess needs in order to connect them with appropriate services.”

As the pandemic hit in early March, many organizations had to close down or curtail services to ensure public safety. Miriam’s Kitchen remained open for essential services using safety measures prescribed in a new age of physical distancing.

“Our CEO felt that as so many other sites were closing, Miriam’s Kitchen needed to be available to people experiencing homelessness to provide warm meals, clothing, sleeping bags. It was a stripped-down version, serving our community in outdoor tents,” says Rahn, who requested to stay on as a volunteer.

Was he concerned about his safety? “I had a natural level of concern,” he says. “But as someone not in high-risk health categories, I felt called to be there for those who don’t have a home to isolate in, whose basic hygiene needs are not being met, who are hungry.”

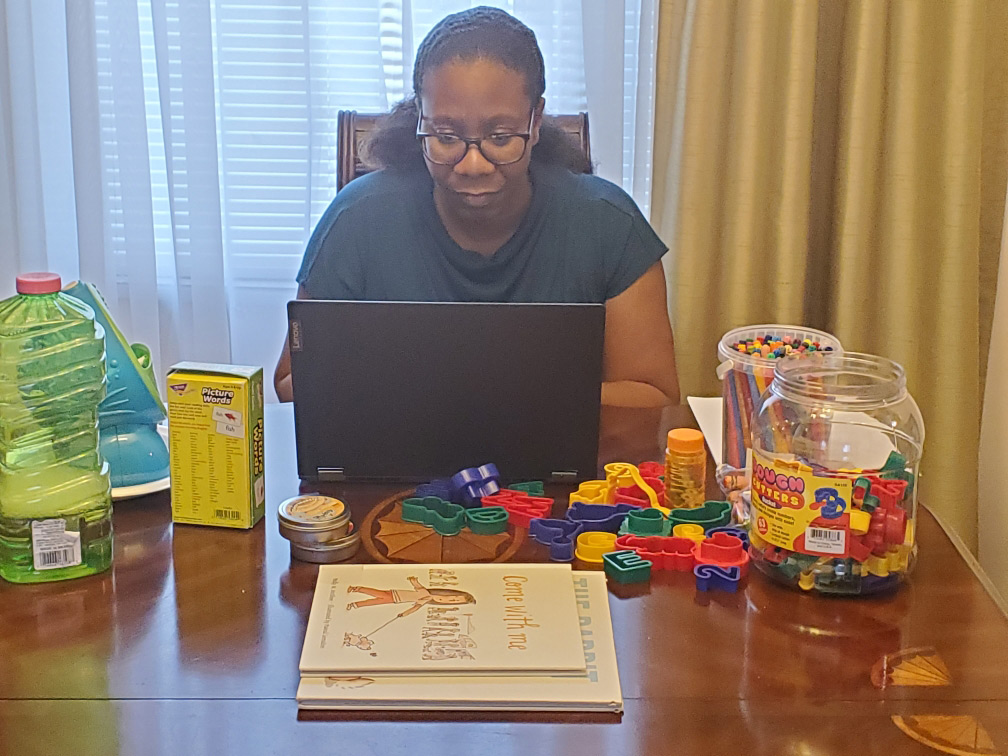

As she neared completion of her graduate program this spring, M.S.W. candidate Jessica Wiley had to quickly pivot to continue her field placement. Wiley was working at College Park Youth and Family Services, an agency within the Maryland Association of Youth Services Bureau, facilitating teen groups from local schools onsite at the agency, as well as play therapy for younger children. In early March, when it was determined that schools would physically close, Wiley had only a day to collect her files and consult with others at her agency to establish protocols for working with children and families through telehealth therapy.

“I felt so fortunate that I could continue my field placement even though it would be quite different,” says Wiley. “You have to be creative to engage in play therapy virtually. There was a lot of sharing among supervisors and staff at the agency, as well as my faculty and fellow students, to make the pivot work.

“That’s what social workers do. We meet our clients where they are at that moment, and as the crisis hit, we shifted our work to address our clients’ immediate needs. For instance, I was now beginning my therapy sessions with family check-ins. Did they have resources for homeschooling? Were parents’ jobs affected? Was food insecurity an issue?”

The National Catholic School of Social Service (NCSSS) has rallied as a virtual community, most notably offering Friday afternoon teleconferencing for all students and faculty, with a unique topic each week related to the role of social workers during a pandemic. “These Friday seminars keep the connections within our community strong during a time of physical distance,” says Marie Raber, interim dean. “It’s a time of learning, but also of dialogue. Students know they can bring their concerns to these online gatherings.”

“This crisis has broadened the horizons of our students,” says Roslynn Scott-Adams, assistant dean and director of field education and professional development. “It has forced them to more urgently connect what they are learning in classes, especially when it comes to issues of social justice. I had one student tell me as a result of the pandemic, she now wants to shift her focus from a clinical career to one in public health and health care policy.”

“This will only make our students stronger, more resilient,” adds Danielle Parker, assistant dean and director of online field education. “They have had to adjust. And in doing so, they’ve had a unique window into the profession. Social workers meet the critical needs of the moment.”

“There has definitely been a silver lining,” says Wiley. “I’ve had to reach out and search resources, be creative, ask more questions, and stretch myself. It has shown me that NCSSS is a life-long community. That’s been helpful in dealing with the loss of a formal graduation ceremony.”

The pandemic has reaffirmed Rahn’s decision to become a social worker. “The needs of vulnerable oppressed populations have become even more extreme,” he says. “They need someone to walk with them, to connect them with resources. And even with their suffering, there are joys and blessings. They are capable of some of the most beautiful expressions of gratitude I’ve ever encountered.”