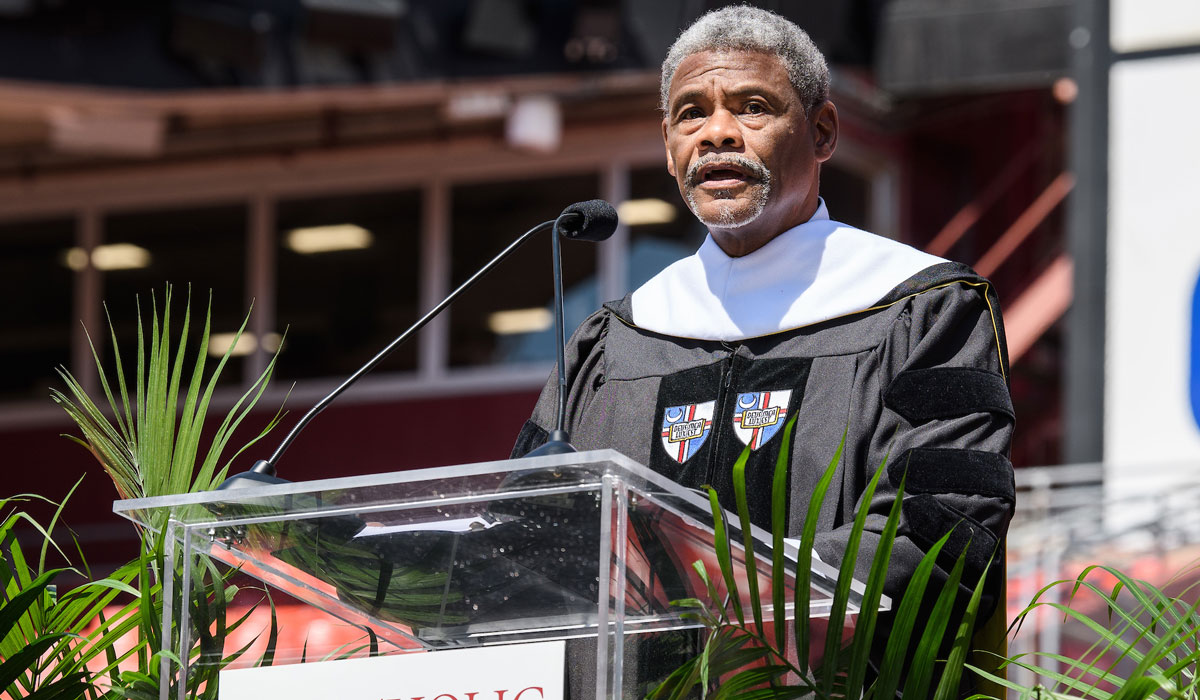

132nd Annual Commencement Remarks

FedEx Field

Greater Landover, Md.

William Chester Jordan

May 15, 2021

I want to thank President Garvey and the Board of Trustees of Catholic University of America for the honor of the Degree of Doctor of Humane Letters and for the privilege of delivering the Commencement Address today.

Higher education is a precious commodity. As a medieval historian of France, I thought it might be of interest to tell you a story today of the early university, an institution invented in the Middle Ages, which would suggest that higher education was as precious in the thirteenth century, the period I study, as it is now. Yet, as now, it was not available to everyone on an equitable basis.

The story begins on October 9 in the year 1201 when a child was born in a village in the region then known as the Rethelois, the region in the far north of France near the present-day Belgian border extending from the castle town of Rethel on the edge of the great and still formidable forest of the Ardennes. The parents were two low-born peasants, “villeins” or serfs in the language of the time. Unfree people. Their baby boy was christened Robert. As he grew up he showed signs of extraordinary intelligence, although what he chose later on to remember about his time at the village school was the rambunctiousness of his school mates. If village life had its pleasures, it also had its limits. A boy like Robert could make more of himself, as his parents knew, if he successfully sought a professional career. No doubt it was a struggle for them to meet their goal for their son, but they did succeed in obtaining freedom for the boy, probably through a healthy payment in cash, kind or labor to the lord who owned them.

In Robert’s case he began to read for the pastorate, probably with his local parish priest, and, then, exploiting a wonderful opportunity, he became a scholarship student at the College of Rethel in Paris, one of the many small associations of students supported by regional lords, in this case Count Hugh II of Rethel, who employed people (boys) educated at the college to help administer his estates.

Robert, however, did not return home to a career as an estate manager, personal secretary, lawyer or village priest. His brilliance shone as a student, and he was inspired to pursue his studies in the higher faculties of the still quite young University of Paris. After he received his degree as a master, which licensed him to teach, he was appointed to the faculty himself. Soon Robert’s renown was such that he came to the attention of the French king, Louis IX (Saint Louis, as he later came to be known), and to the attention also of the king’s formidable mother, Blanche of Castile, and that of a host of other powerful figures in the royal circle, including Louis’s wife Queen Margaret of Provence. Robert himself soon emerged as one of the king’s closest confidants—helping to articulate policies of moral reform in government and otherwise crafting guidelines meant to assure the just administration of the laws.

Yet, he never forgot or was allowed to forget where he came from. Aristocrats typically looked down on peasants, especially those from a region as underdeveloped and poor economically as the Rethelois, much as East Coasters now make crude and hurtful jokes about the cultural practices and accents of Appalachians. And perhaps most condescendingly, they made wicked fun of the occasional rustic, like Robert, who made good. Despite his closeness to the king, Robert had to endure this swaggering snobbery to his face at times as well as in a popular song ridiculing him for advising King Louis to put more constraints on wanton aristocratic behavior. Robert obviously thought that it was worth suffering this disrespect from those who looked down on him. For only among courtier aristocrats and others in the royal circle was it possible for him to work as effectively as he desired for the common good, despite the disdain that showed on the faces of many toward his low birth. Robert never opted to skulk back to his birthplace and curse those who mocked him.

In Paris, in this atmosphere, Robert came up with an extraordinary plan. As he had benefitted from his time at the small College of Rethel, he thought it might be useful to establish another small boarding house to lodge students who, as was once true for him, had barely enough money to pay for daily meals and minimal lodgings in the expensive housing market of Paris. He shared this idea with the queen-mother, Blanche of Castile, a woman who is critical to this story, for it was she, it appears, who prompted Robert to think bigger. Why stop at a boarding house, a few scant rooms, furnishings and maybe meager meal subsidies? Why not, if he could find benefactors, establish a full-fledged college as a constituent part of the University of Paris, one that catered to the needs of poor folk from his region and from others as well, who otherwise would have few opportunities to study in the capital? Why did the attendees at the University, as they were at the time, have to be the children of aristocrats? The queen-mother did not much care for them or they for her. And they made merciless fun of her in their drunken songs. But Robert’s college would be different. The students there would appreciate opportunities offered to them that they had never before thought might be in their grasp. Amid these hopes and circumstances in the 1250s was born the greatest and most enduring of the Parisian colleges, the Sorbonne, named after Sorbon, the village where Robert was born.

There is a lesson here, one supposes, for our own time—think of the discourse on diversity and of the clarion call to offer top-quality education to eager first-generation college attendees and the concomitant desire, often expressed, to reach out to those who have the intellectual capacity and the dreams but perhaps neither the means nor sufficient preparation to attend institutions of higher education. The story of Robert of Sorbon, however, does not come to an end with the establishment of a college for financially at risk students, often linked in the scholarship a little too simply with King Louis IX’s generosity. In fact, with the king’s financial resources at the time otherwise committed, and though he was destined to contribute to Robert’s enterprise, it was many years later before he could do so. In the early years, the first six or seven, it was up to Robert to see that the fledgling institution survived. So Robert had to fund raise. And it was an extraordinary effort he undertook.

He prepared the rules and procedures (the statutes, as they were called) for the new institution and assumed its headship, a position known as Provisor, rather like being president, provost, dean of the faculty, and director of development all in one. He designed and instituted a preparatory or remedial program for admitted students who came inadequately or ill-prepared. Books he had accumulated during his time as a student and professor became the core of the new college’s small library. And then he started his solicitations. He succeeded in getting his friend, another royal adviser, William of Chartres, once as poor a child as Robert had been, to convey a number of Parisian properties to the Sorbonne. He had done well for himself in the real estate market before he became a Dominican friar. Indeed, what has never been stressed before is the background in general of the early donors to the Sorbonne, the ones Robert so assiduously cultivated. These were men, once impoverished youths, whose talents local persons of influence had first noticed and brought to the attention of mentors and potential patrons. The queen regnant’s physician, Robert of Douai, was another friend Robert of Sorbon had made at court. They hit it off well and could have swapped stories of what it meant to struggle from humble beginnings to almost the pinnacle of influence by serving in the king’s household. Those stories would have recalled also the far more and far less fortunate fates of those who had struggled hard, yet failed. But Robert of Douai had been lucky enough to be selected as Queen Margaret’s personal consulting physician because his medical practice in Paris was so renowned. In achieving this success he had acquired a vast fortune—a fact deeply resented by aristocratic types who hired minstrels to compose and sing derisive verses about him, too. This evidently only made him more committed to Robert of Sorbon’s enterprise. In a wondrous act of ‘planned giving’, Robert of Douai left a bounty in his will for the new College of the Sorbonne. When he died on the 25th of May 1258, the Sorbonne became the recipient of a testamentary bequest of 1,500 pounds, a genuinely princely sum at the time. He also bequeathed his horde of scholarly books to the nascent library, turning it overnight into a major research center.

Two other pivotal persons, to conclude this story, who provided additional endowments for Robert of Sorbon’s enterprise in the earliest phase of its existence were Geoffrey of Bar and William of Bray. Their social origins mirror Robert of Sorbon’s as much as those of William of Chartres and Robert of Douai. Geoffrey of Bar, though he rose to be dean of the cathedral chapter of Notre-Dame of Paris, to serve as an adviser to King Louis IX, and to hold the office of cardinal-priest of Santa Susanna in Rome, was born into a commoner family living in abject poverty. And William of Bray was from another family of inferior social status and deep economic want; yet, he, too, found his way to the deanship of the cathedral of Notre-Dame of Laon, where he also served as a legal expert, and from there to Louis IX’s court, ending his career as cardinal–priest of San-Marco.

All of these men would have served as examples for the impoverished students who came to the Sorbonne in the thirteenth century, examples of what hard work and erudition could accomplish. Their determination that the benefits of higher education should be widely distributed should motivate and activate us today. One of the reasons I guess I so like the story I have told today is that it evokes some memories of my own: caring parents who worked hard and doubled their efforts to earn enough to send me off to college and, then, the experience of college itself, which widened my horizons and enriched my understanding of the human condition through books of history and philosophy, through novels and poetry, and through interaction with inspiring and nurturing mentors and other people from traditions and walks of life I had never encountered before. In some ways, as a friend of mine once put it, the multiple experiences and many books of a good education in the best case scenario lead to confusion, but a higher state of confusion, far more productive than the confusion begotten of ignorance, prejudice and bigotry. The preparation that Robert of Sorbon received at the College of Rethel and that propelled him to continue his education in the higher faculties in Paris also model mine, with teachers urging me on, which sent me to Princeton University, and which made possible a fulfilling career as a professor. But most important, as college was liberating for those students in thirteenth-century Paris I have spoken to you about, it was profoundly liberating for me. It made me, I believe or at least I hope, a more humane individual. You students, who are graduating in this exercise today, now have the benefits of so much learning ahead of you. Never ever forget how you acquired it, and I urge you to always strive, to the extent you can, to preach the beatitude of education to those young people whom you encounter throughout your lives. Thank you and good luck to you all!