At the World Day of Migrants and Refugees Mass in January 2018, Pope Francis urged people the world over to welcome the stranger. “Migration today is a sign of the times,” he said. “Every stranger who knocks at our door is an opportunity for an encounter with Jesus Christ, who identifies with the welcomed and rejected strangers of every age” (Matthew 25:35-43).

During his weekly General Audience in St. Peter’s Square a year earlier, the Holy Father said, “Christ asks us to welcome our migrant brothers and sisters with arms open wide.” It was the start of a worldwide campaign, “Share the Journey,” to walk in solidarity with migrants and refugees.

Caritas Internationalis, a worldwide charity of the Catholic Church, is the primary sponsor of the campaign along with the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB), Catholic Relief Services, and Catholic Charities USA. The campaign encourages people to encounter migrants and listen to their stories.

The USCCB has supported and embraced the message with its vision of “a world where immigrants, refugees, migrants, and people on the move are treated with dignity, respect, welcome, and belonging.”

As the national university of the Catholic Church in America, we too are “sharing the journey.” In this issue we present stories of students, staff, faculty, and alumni who are answering the call to join in the journey with those seeking refuge and a better life.

We realize the topic of immigration reform is fraught with opposing views and no easy solutions. In this immigration-themed issue of the magazine, our objective is to look first at the humanity underlying the debate.

“We as holy people are called to achieve Miracles of love in the name of Jesus Christ.”

He remembers all too well what it’s like to be an outsider. When he first came to the United States from Bogotá, Colombia, to pursue his doctorate at The Catholic University of America in 1991, Bishop Mario E. Dorsonville, D.Min. 1996, spoke very little English and knew almost no one.

Looking back on that time, he is grateful for the patience and love of his professors, who helped him through the difficult course material as he adjusted to life in a new country. Among the many lessons they passed to him, he says, was the importance of listening.

The program “helped me to understand how important it is to read the happiness or the tragedies of people across their own lives,” Bishop Dorsonville says. “If you really want to accompany people, you have to learn how to listen to them to understand them better.”

Bishop Dorsonville’s dissertation examined Hispanic ministries within the Archdiocese of Washington. As part of his research, he spent time with representatives from many local Hispanic communities uncovering their common struggles and goals.

This passion for bringing together Catholics from different cultures continues to inspire the bishop. Since 2018, he has served as chairman of the committee on migration for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. He’s a vocal critic of U.S. immigration policies and addressed the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Immigration and Citizenship earlier this year to urge Congress to show greater compassion for refugees and immigrants.

The call to serve immigrants and migrants is rooted in his own familiarity with the loneliness that can follow after moving to a new country.

“Leaving the land where you were born is never an easy experience, especially leaving your friends and family and the way you used to express yourself,” Bishop Dorsonville says. “People come to find a sense of peace and some kind of potential future, but sometimes what they find is the worst sense of poverty a person can experience, where they have no face, no voice, and become essentially invisible.”

These challenges are exacerbated, he says, by policies which often dehumanize, demonize, and punish new arrivals.

Catholics can respond to this crisis, Bishop Dorsonville believes, by praying for new immigrants and advocating for their rights whenever possible. He also believes the Church should focus on welcoming immigrants into the community, listening to their stories, and incorporating them into local life whenever possible.

“The only way the Church can be meaningful in today’s world,” he says, “is to remember that we as holy people are called to achieve miracles of love in the name of Jesus Christ and to be the engine of the living Christ.” — K.B.

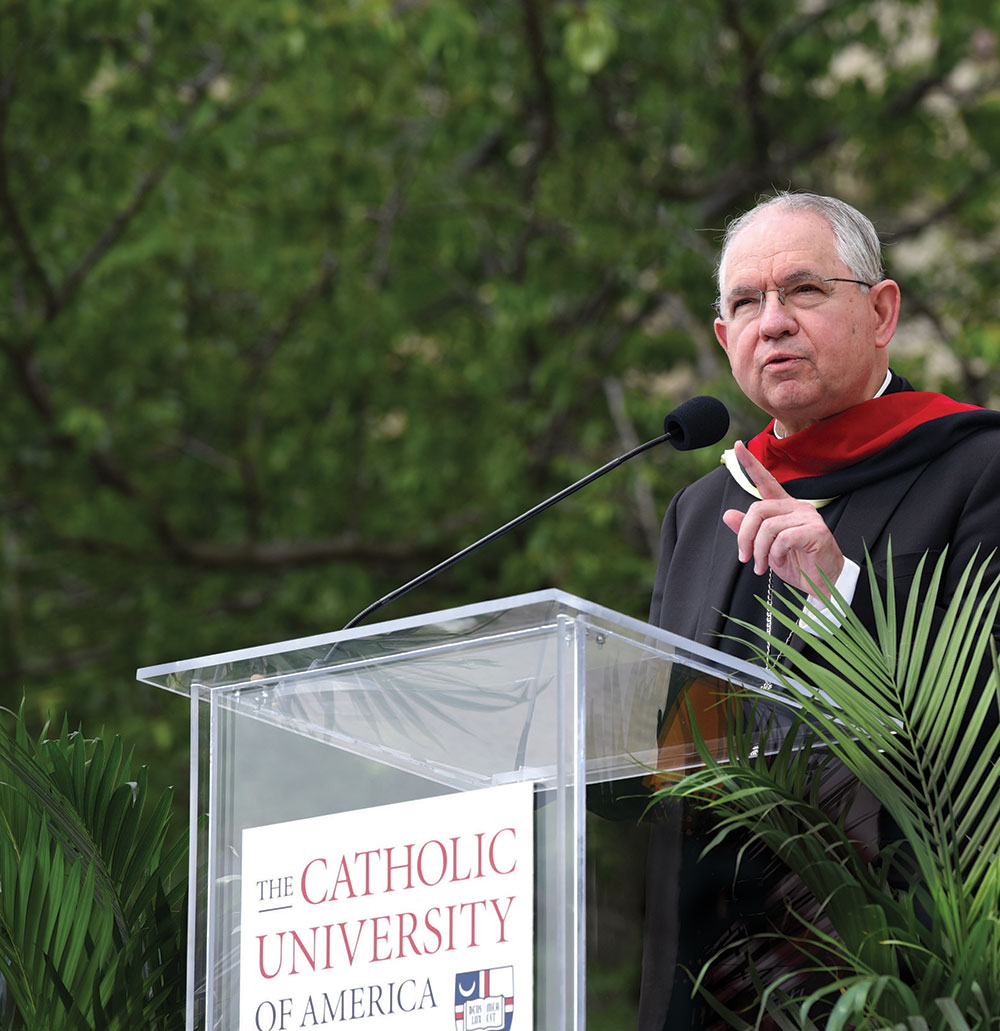

Archbishop José H. Gomez

Archbishop José H. Gomez“We are talking about souls, not statistics.”

As archbishop of Los Angeles and president of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB), Most Reverend José H. Gomez is a leading voice on immigration. He is also a member of the University’s Board of Trustees, and has been a welcome, frequent speaker on campus. He delivered the 2018 Commencement address at a ceremony in which all the honorary degrees recognized immigrants. In 2017, he was invited by students to discuss immigration. “For me and the Catholic Church,” he told them, “immigration is about people. We are talking about souls, not statistics.”

The archbishop grew up in Monterrey, Mexico, and is a naturalized U.S. citizen. Today, he leads the largest archdiocese in the United States in one of the nation’s most diverse metropolises.

While on campus last spring to deliver the 7th annual lecture in the Hispanic Innovators of the Faith series, he took time to answer a few questions for CatholicU magazine.

“God created us as his children, regardless of the color of our skin or the place of our birth,” he told us. “We are all brothers and sisters in Christ.” Immigrants, he said, “make beautiful contributions to our society. Our history shows that.”

Immigration reform must reflect the realities of the world today, Archbishop Gomez added. “People have the right to move to seek safety and better opportunities for themselves and their children. They want to work legally. We don’t offer them legal options. This is a moral issue. At the same time, we must ask ‘Why would people risk their lives to leave their country, their family, their friends? What can we do to address the instability, violence, poverty, and lack of healthcare and education in Central American countries? What role have we played in causing these problems?’”

In his 2013 book, Immigration and the Next America: Renewing the Soul of Our Nation, Archbishop Gomez wrote that “since the days of Jesus and the apostles, Catholics have always understood themselves as men and women called to serve God in the poor, in the least of our brothers and sisters. …

“So we can’t choose to love some but not to love others. We can’t justify having less compassion for those who don’t have the right documents.” — E.N.W.

“They cared for me as much as I cared for them.”

On All Souls’ Day in November 2013, bishops from Mexico, New Mexico, and Texas celebrated Mass at altars on each side of the U.S. border. When it came time to share the sign of peace, Amanda Ceraldi, B.A. 2014, reached through the fence to touch the hands of people she had never met, but who, as a population, she had come to love.

“I studied abroad in Rome in fall 2012 and before returning home, I attended Christmas Eve Mass at the Vatican. It was a profound experience. But the Border Mass — that was life changing,” she says. “I believe it was the day I fully understood my calling.”

The Border Mass, held annually since 1998, capped several months of discernment for Ceraldi that began the previous summer. A theology major, she was one of five undergraduate students who embarked on the University’s first Campus Ministry-sponsored border immersion trip led by Sister Ruth Harkins in May 2013. In El Paso, Texas, they worked in fields alongside migrants, volunteered at shelters, met with community leaders, and shared meals with those seeking refuge and the citizens working to help them.

The students were so moved by the experience that when they returned home they began to plan a “CUA on Tap” event to share what they experienced with the University community. In preparation, Ceraldi and a fellow student returned to El Paso later that summer to interview some of the people they met on the border trip for a short movie they would produce for the fall event.

They invited one of the friends they made on the immersion trip as their guest speaker. The program, says Ceraldi, remains “one of the University’s most well attended CUA on Tap events.”

Among the more than 300 people who attended was Ceraldi’s mom. “I grew up in a house in which we were not touched by the plight of immigrants,” Ceraldi says. “Like many Americans, some of my parents’ opinions were formed by misinformation or lack of information about the experience of migrants. After our presentations and our film, my mom came to me with tears in her eyes and told me I had opened her mind. I can’t express how powerful that was, as a daughter, to know that I had impacted my parent’s viewpoint.”

Her path as a student at Catholic University led her to Guatemala, where she lived for three years after graduation working in an orphanage for poor and marginalized children. Her mom and dad, sister, and three best friends visited during her time there. “My students called my parents ‘mom and dad.’ My mom still has their drawings hanging in her office.

“The people of Guatemala cared for me as much as I cared for them,” she says. “We hear the rhetoric of ‘caravans of criminals,’ but that was not my experience. I knew children who lost parents, and parents who lost children to extreme poverty and to gang violence and corruption. That’s why people leave their homes and families to make a treacherous journey where they face abuse, robbery, and incarceration. In the immigration debate, we need to talk more about these push factors that force people from their home countries.”

After Ceraldi returned to the U.S, she entered a transition program for women who have been engaged in long-term service. Called After Volunteer Experience, it is run by the Sisters of Charity of Cincinnati in Anthony, N.M. There, she reflected on her experience and readjusted to American life, a radical change from the abject poverty that surrounded her in Guatemala.

And she continued to serve. Every Thursday, Ceraldi volunteered at Proyecto Santo Niño, a clinic for children with disabilities, in Anapra, Mexico. She grew close to a family whose daughter has Down syndrome.

She would cross the border on Wednesday mornings and spend the day with this family and stay at their home overnight before volunteering the next day. “I became good friends with the mom, who was 25 at the time, just a year younger than I,” she says. “We came from different backgrounds, but we laughed at the same things. They lived in a three-room concrete house. The roof leaked and it could get up to 110 degrees during the day in the home. Sometimes I would take their younger son to school. They cooked for me and showed me loving hospitality. And just like the people in Guatemala, they welcomed me into their family.”

When she completed her transition period, Ceraldi was happy to return to the East Coast and “the incredible opportunity to be back at the very place that formed me.” In July 2018, she accepted a position with Catholic University’s Office of Campus Ministry as associate campus minister for women’s ministry and pro-life hospitality. “Now I get to walk with students as they find their own calling, whatever that may be.” — E.N.W.

Deacon Stephen Kaneb

Deacon Stephen Kaneb“The Catholic Church serves as a leader in pushing for reform.”

Deacon Stephen Kaneb had students like Amanda Ceraldi in mind when he decided to support the University’s border immersion trip program. “I’ve witnessed the profound effect these experiences have on people’s lives, particularly students, who see the world through a new lens,” says Kaneb, a member of the University’s Board of Trustees and a permanent deacon at Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal Parish in Hampton, N.H.

Through his work with Catholic Relief Services, Kaneb has visited vulnerable populations in the West Bank and El Salvador. When he heard about the Campus Ministry border immersion trip, he gladly signed on as a donor. In 2018, he accompanied the student group and their leaders to the U.S.-Mexico border.

“We visited the office of Catholic Charities of Southern New Mexico for an information session about the immigrants’ struggles,” he recalls. “We were one of four college groups present, all making trips to the border during spring break. I loved being with all of these young people and sharing their curiosity, which increases the compassion necessary to understand how many challenges surround immigration.”

Some of the most beautiful moments on these trips, says Kaneb, come unexpectedly “when you lock eyes with someone suffering and just know that God put us together for a reason. He loved each one of us into existence and knew each of us by name long before we were born.”

Kaneb has a personal connection to Latin America. Two of his five children are adopted — biological brothers from Guatemala. “Two years after the second adoption, we visited Guatemala as a family. We now can better understand the culture of our sons’ country of origin. And we more clearly see that America is actually one continent.”

The federal government will eventually enact comprehensive reform, says Kaneb. “We were getting close 20 years ago, but then 9/11 changed the country’s priorities. Both nationally and internationally, the Catholic Church serves as a leader pushing for reform. We strive with both parties to advocate for solutions that respect both the nation’s sovereignty and the human right of people to migrate.” — E.N.W.

“These are the stories of human beings.”

As the moderator of the University’s annual U.S. border immersion trip, Sister Ruth Harkins, I.H.M., has prayed in the pepper fields of Hatch, N.M., after watching the backbreaking work of migrant workers. She’s spoken with immigrant families about their everyday struggles to make ends meet without a clear path to citizenship. She’s visited shelters for unaccompanied children and monitored immigration court proceedings. And she’s even participated in government-sponsored tours of the U.S. border and migration detention centers in El Paso, Texas, and Chaparral, N.M.

During her first trip to El Paso in 2013, Sister Ruth remembers being particularly shocked by the number of children she saw in the shelters for new migrants.

“I’ll never forget that, being in the shelter with these children from all over Latin America, speaking all of their different languages and so scared,” Sister Ruth says. “Especially coming from Washington, you hear so much about immigration in the news, but what you hear hasn’t always reflected reality. You aren’t hearing the real stories of why families come, why they are here, and what violence they might be escaping.”

Exposing students to the human faces of immigration is a priority of the border immersion trips, which take students on an educational pilgrimage through El Paso and Las Cruces, N.M., introducing them to communities and people directly affected by immigration policies today. Sister Ruth also teaches the accompanying Theology of Mission course, which combines lessons on Catholic social teaching and theology with an introduction to the history of migration and current immigration laws.

For Sister Ruth, who has been working as the associate campus minister for graduate and professional students since 2013, the trips have become a part of her vocation, calling her back to the charism of her order, the Congregation of the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, which was founded to serve the poor and the abandoned — especially immigrants. Prior to coming to Catholic University, she worked as a high school teacher and guidance counselor, a vocations director, and a minister to those with HIV and AIDS.

“At this moment in time, I’m being called to journey with the students as they encounter the face of God in the stories of migrant people,” she says.

Sister Ruth says she’s inspired by the growing number of students, faculty, and staff members who are interested in participating in the border immersion trips. Each experience is unique, she says, and they have become increasingly diverse, with some students coming to learn about the immigration experiences of their own parents and grandparents. Others aren’t sure where they stand on the immigration debate and are taking the courageous journey to see the realities firsthand.

“Students come on these trips for their own reasons,” says Sister Ruth. “It’s amazing to see them struggle with all that they see and experience as they try to form their personal response to the current immigration crisis.”

Sister Ruth believes students can become a beacon of hope for migrants as well as for those who have grown weary of changing immigration policies over the years. She has been inspired by the ways in which students have been transformed by their experiences, whether it’s continuing to do service work or even pursuing careers in the field of immigration. For her, the issue of immigration is more than a political one. She believes it’s an issue of humanity.

“My hope is that this will become a central issue for the entire University so there will be outreach not just through the border trip, but also locally in D.C.,” she says. “I think it’s really important to show students that this is the reality of what’s happening. It is not always reflected this way in social media or the news. These are the stories of human beings.” — K.B.

Deacon Elmer Herrera-Guzmán

Deacon Elmer Herrera-Guzmán“This issue isn’t about a particular country, immigrants, or citizens. It’s about the children of God.”

Nobody wants to leave their country in order to be rejected elsewhere,” says Deacon Elmer Herrera-Guzmán, a graduate student in sacred theology and divinity at Theological College (TC), the national seminary at Catholic University.

When he was 12, Herrera-Guzmán migrated to the United States from El Salvador. Arriving in Dallas, Texas, he and his family eventually reunited with his father, who had arrived in the U.S. earlier.

Though the Salvadoran Civil War ended in 1992, Herrera-Guzmán’s native country is still scarred by violence. Help is needed, he says, to stabilize the region.

“These are potentially good countries,” he says, “but they deal with violence, and in El Salvador, many children grow up fatherless due to the civil war. These children grow with this hurt that expresses itself in society.”

Despite everything, he believes change is possible.

“I know El Salvador can be great,” he says. “But people who can create change in my country are leaving. My mother and father were middle class people, both teachers, but were suffering and had to leave a life as professionals to work in janitorial services in the U.S.”

When immigrants come to the U.S., Herrera-Guzmán explains, they often lose not only their dignity, but their voices. “People are not being heard because the language is not the same. They’re speaking pain.”

He says the Church provides a sense of stability for many immigrants, and in his youth it helped him feel that he was part of a community. After graduating from high school, Herrera-Guzmán worked as an insurance agent and taught children in his parish. But he felt called to a deeper sense of fulfillment, so he started learning about the priesthood.

It wasn’t until one day he got lost while driving in Irving, Texas, that he found his way to where he is now. “I saw a statue of Jesus outside one of the buildings. I walked into the main office and asked what this place was? They said it was a seminary for Catholic priests. I ended up getting lost and landed in a seminary where I started my vocation,” he says.

Now a transitional deacon, Herrera-Guzmán came to TC for his years of formation and academic studies. Following graduation in May, he will be ordained a diocesan priest for the Diocese of Dallas, where he is prepared to serve and teach with compassion, especially when ministering to the immigrant community.

He helped create TC’s Hispanic Affairs Committee of the Student Government Association. The committee equips future priests with cultural knowledge, language, and liturgical skills to better shepherd the burgeoning Latino community in the American Church.

“How the Church and the community communicate is key,” he says. “We need to know how to minister to people who are being rejected by society.”

In Herrera-Guzmán’s view, his parish and many others are helping immigrants by providing vital resources. “My parish brings in immigration lawyers for anyone who has questions. Another parish in Dallas provides facilitators to help immigrants fill out their paperwork. At the end of the day, this issue isn’t about a particular country, immigrants, or citizens. It’s about the children of God.” — G.O.

“How can we intervene for suffering families?”

Professor Sandra Barrueco has made helping immigrants her life’s work. Now in her 16th year at the University, Barrueco engages with immigrant children and families on multiple levels, overseeing psychological assessment and intervention, leading research projects, and recommending policy, all while managing a busy teaching schedule.

Barrueco, director of clinical training in the Department of Psychology, is conducting the first nationally representative study of its kind with migrant families, most of whom are immigrants. She also teaches in the University’s multidisciplinary Latin American and Latino Studies program. Barrueco credits her students with bringing high levels of skill and involvement to their classes.

She and her students have traveled around the country to work with families associated with Head Start, the nation’s largest support program for impoverished children. One of her policy briefs, on how schools and early intervention programs do outreach to immigrant families, is frequently referenced, and her research was cited in the creation of national standards for diagnosing bilingual children.

“We are very much at the forefront of immigrant issues,” says Barrueco. “Our research is making an impact on, and improving, national policies and practices. I get to peek under the hood at various universities, and it really is different here. There is a more engaged, insightful, and advanced conversation at Catholic University, and you can sense a strong, underlying dedication in the classroom — perhaps due to some of the experiences that the students themselves bring, whether they’re immigrants or not.”

Many immigrant families are subject to stress on various fronts. It begins with situations in their home countries that become unendurable, and continues on the journey to their destination country and afterward.

“You and I would not be leaving our families and moving across the world unless there was something horrible happening,” Barrueco says. “During the journey, they often experience more trauma. And then, as they get their families up and going here in the U.S., the stresses trickle down to their young ones.”

Discrimination, she adds, erects many barriers to immigrants and their families. Poverty poses significant problems; housing and language learning present hurdles, too. In families that have been separated, suddenly being reunited with other family members can also give rise to many issues.

Stressors like these can take an even greater toll on the descendants of immigrants, through what’s called the “acculturation paradox.”

“People think that the first immigrants are the ones who face the most challenges, but actually it’s the next generations after that,” Barrueco explains. “Those children start to have more mental health issues, and more health outcome issues in general. Not all immigrant families are suffering, but a good deal are. How can we intervene?”

Hailing from an immigrant family, Barrueco has an insider’s perspective on some of the experiences that are important to take into account in understanding how to improve outcomes for children and families.

“It is very helpful to be multilingual, to be multicultural, to bring that to the table as a psychologist and a professor,” she says. “It boils down to being able to make a substantive contribution to the lives of immigrants, nationally and internationally, and training students to do that work as precisely and rigorously as possible.”

Despite her concern for the problems that immigrant families face, Barrueco is quick to point out that they also possess many strengths, resilience among them.

“These are families that have gone through a lot, and they’re trying to be very strong,” she says. “The main factors that immigrant families say keep them strong are belief in God, working hard for a better life for their families, and being completely dedicated to their children’s future. Those are the three factors that keep them going, day in and day out.” — G.V.

Dylan Corbett

Dylan Corbett“Our border communities are among the safest in the nation, not in spite of immigrants, but because of them. They strengthen and enrich our communities.”

Along the U.S. southern border, where communities live the realities of immigration every day, Dylan Corbett, Ph.B. 2004, works to provide aid, solidarity, and solutions guided by Catholic principles of social justice. He is the founding director of the Hope Border Institute (HOPE), a faith-based research, education, and advocacy organization that focuses on border issues. Previously, he worked for the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops in its Department of Justice, Peace, and Human Development.

Corbett says his philosophy degree “gave me a strong foundation in critical thinking and the idea that faith is fundamental to building a better world.” Here, he offers his perspective on immigration-related topics.

MISCONCEPTIONS

“The truth is we’ve been doing two things for a long time that transcend the current administration: criminalizing migrants and militarizing the border. Migrants are not threats. They are vulnerable people. I live in El Paso. Our border communities are among the safest in the nation, not in spite of immigrants, but because of them. They strengthen and enrich our communities.”

COMPREHENSIVE REFORM

“Most people would rather stay in their home countries. But they are forced to leave — many as a matter of life and death. We have to address the root causes: corruption and violence, food insecurity, drought, climate change, and unfair trade policies.

“Within the U.S., we must find a path to citizenship for the more than 11 million people who live, work, and raise their families in the shadows.

“We must end inhumane practices such as prolonged detention, detention for profit, and family separation. A top priority for HOPE right now is dealing with the repercussions of the 2019 Migrant Protection Protocols, otherwise known as “Remain in Mexico,” which circumvents the Refugee Act of 1980 that allows asylum seekers refuge in the U.S. “Remain in Mexico” instead forces refugees awaiting a determination to stay in Mexico where, according to the Department of Homeland Security, they “receive appropriate humanitarian protections” and access to an attorney. That’s not what is happening. Migrants left in Mexico are exposed to criminal predators, and often have no access to shelter, healthcare, or employment. And the best they can hope for is a mass hearing, often under a tent, that delivers no real hope of being granted asylum. We should uphold the U.S.’s historic and legal commitment to refugee and asylum seekers.”

THE ROLE OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH

“The Church has witnessed border shifts for centuries and what has remained a constant is the centrality of the human person. Today, Pope Francis is clear on where we stand as Catholics — we welcome the stranger. We know that the immigration debate is not about abstractions, but about people with names and faces and hearts, who are loved by God.

“The Church is an important presence providing direct humanitarian assistance and advocating for comprehensive immigration reform. HOPE was working with a mother and her daughters, asylum seekers who were fleeing direct threats and violence in their home country. The family’s 12-year-old was undergoing treatments for cancer when the mother learned she would be deported. She was faced with the decision to leave her children or take them with her, knowing her daughter would not be able to continue treatment in their home country. These are the difficult decisions immigrant families face every day. Bishop Mark Sietz of El Paso accompanied the mother to a meeting with deportation officers and was able to influence them to keep this family together in the U.S.”

PARTNERSHIP WITH CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY

“For several years now, we’ve welcomed Catholic University students, faculty, and staff during their spring break. They come with open minds and a desire to learn and serve. As future leaders studying in our nation’s political center, they have the potential to provide critical advocacy and shape policy.”

WHAT GIVES HIM HOPE

“There are a lot of things that separate us — a wall, rhetoric, inhumane policies, fear, and anger. But every day, in our border communities, I see an amazing network of advocates, attorneys, and community and Church leaders working tirelessly to bring us together for justice and meaningful reform. That gives me hope. — E.N.W.

“Life is full of twists and turns.”

On the Feast of the Immaculate Conception last December, Javier Bustamante, director of Catholic University’s Center for Cultural Engagement (CCE), gathered with students in St. Vincent’s Chapel to celebrate Simbang Gabi, a traditional Filipino Mass. Afterward, they walked from the chapel to the Pryzbyla Center singing Christmas carols and reflecting on Mary and Joseph’s journey to Bethlehem. This was the Mexican tradition of Posada. At the Pryz, they enjoyed Parranda Navideña, a cultural treasure of Puerto Rico featuring food, music, and dance.

As CCE director, Bustamante’s job is to recruit, welcome, and mentor students from diverse backgrounds, and provide cultural education and experiences for members of the University community. His office is embedded within the center’s student lounge in the Pryz, and he often accomplishes his work to the rhythm of laughter and chatter just outside.

“It’s a place where students come together to share stories, make friends, study, lift each other up, and do the occasional napping,” Bustamante says. One of CCE’s recent initiatives is Take Flight, a program that provides mentorship and support for first-generation students as they transition to college life.

“I love watching our students become campus leaders, sharing the stories of their cultures and their vision for a more welcoming America,” says Bustamante. He often shares his own story with students as a way to show them “life is full of twists and turns.”

He came to the United States as a teenager in 1994 from Peru. “The country was immersed in political conflict. A young man walking on the street could disappear,” he says. “My godfather, who lived in Los Angeles, asked my father if he could take me to live with him. I imagined I would live in a skyscraper and play soccer every day after school. I thought I would return every year to Peru to see my family, just like my godfather did. But he had a green card.”

It was not until 2009 that Bustamante, who became a U.S. citizen in 2017, was able to get his green card and make his first visit home. “My sister was two years old when I left. She was 18 the next time I saw her.”

Living in a Mexican community in Los Angeles, Bustamante became active in his parish and began to lead youth groups, an interest that has defined his career. Because he had overstayed his visa while wading through the lengthy, complicated process of attaining legal status, he was an undocumented immigrant when his life took a turn. “I was on top of the world. My youth ministry program was thriving. I had completed two years of community college, and had just received a scholarship to finish my degree in history and pastoral studies at Marymount Loyola University. And then, I was detained.”

With several other men, he was shackled and taken away in a border patrol van. He was put in a dark, tiny cell. Near the window, he could see that someone had carved out the words ‘Jesus Saves.’ “I thought about the irony. I cried and raised my fist to God. Then peace came over me and I thought how I had missed my family — maybe this was God’s way of bringing me home.”

Bustamante was moved to a long-term detention center, sharing a cell with a man from Mexico, who had been there for a year. “All he wanted was to see his little girl. We prayed together. I never knew what happened, but I still pray he got to see his daughter again.”

His community and parish members rallied around him and provided a lawyer to gain his release. He was luckier than most, but the detention left its mark. “Even today, when I see a van with a green stripe I am overcome with a wave of anxiety,” Bustamante says.

Bustamante’s application for a green card was delayed for years in the post-9/11 transfer of paperwork to the Department of Homeland Security. Like most undocumented immigrants, he learned to keep a low profile — all while earning his bachelor’s degree and later his master’s degree from Georgetown University.

Before coming to CatholicU, Bustamante served in the Archdiocese of Washington’s Office of Cultural Diversity, working with immigrant communities, including many ‘Dreamers.’

“These young people spend so much time worrying about their family’s status and the possibility of family separation by deportation. They feel they have to be strong for their families. I wanted to offer them a space where they could talk about their fears and be sustained,” says Bustamante.

Not surprisingly, he has definite ideas on the need for immigration reform. “We have to start creating a path to citizenship for more than 11 million undocumented immigrants who want to work legally and raise their families without fear,” he says. “It is the compassionate and Christian response. Good things can only cascade from there.” — E.N.W

Redeate Alemu

Redeate Alemu“A place where we celebrate our differences.”

The Center for Cultural Engagement (CCE) has been like a home for me,” says Redeate Alemu, a junior marketing major. “A lot of us are commuters, and it’s where we go between classes. But it’s so much more. It’s a place where we celebrate our differences.”

Alemu came to the U.S. at age 7 from Ethiopia, where she lived with her grandparents. Years earlier, her parents came to America as winners of the Diversity Visa Lottery, a State Department program that makes visas available, through random selection of entries, to residents of countries with low rates of immigration to the U.S.

Soon after they arrived, her dad was diagnosed with cancer, leaving her mom to work two jobs. Meanwhile, as a little girl in Ethiopia, Alemu only knew her parents through short conversations using international phone cards and the stories her relatives told her. Her dad did recover and the parents sent for their daughter.

“I was excited to come to the United States, but sad to leave my grandparents and family in Ethiopia,” she says. “Family separation is one of the most difficult aspects of the immigration experience. It’s hard to even explain what it’s like to be pulled between two worlds and two sets of people who love you.”

She came to the U.S. speaking Amharic. By middle school she had near perfect English with no hint of an accent. That was the result of hard work and “fear of being bullied.” As she assimilated to American life, she always kept her home country in her heart. “My parents surprised me with a trip to Ethiopia for my 8th grade graduation. It was the best gift of my life.”

Alemu has become a leader on campus. She is vice president of the Black Student Alliance and served as communications student coordinator for CCE. This summer she will head to Redmond, Wash., for a prestigious Microsoft marketing internship.

“I wish others had the opportunities I have had,” she says. “I’m sad for so many whose dream of America is nearly impossible to attain.” — E.N.W.