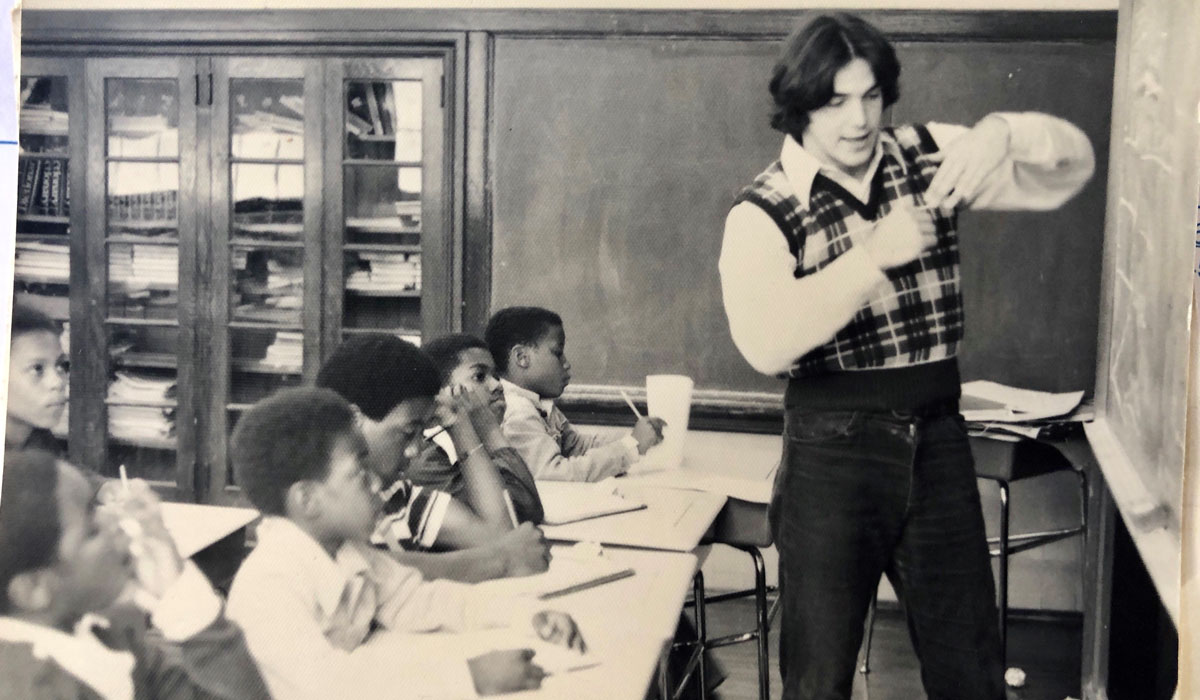

Tim Lisante illustrates a point during his student teaching days in the 1970s.

By Timothy Lisante, Ph.D.

Tim Lisante graduated from Catholic University in 1978 with a B.A. in Elementary and Special Education. Today, he is a New York City Department of Education executive superintendent with 85 principals throughout his citywide network of alternative schools. He serves on the mayor’s Disconnected Youth and Justice Implementation Task Forces. Several organizations serving ex-offenders have honored Lisante, and so has Brooklyn’s Catholic Teachers Association. He has also been recognized as one of the most distinguished alumni from both Holy Cross High School in Queens and Catholic University. We asked him to share some insights he has gained on the job.

Hope shrinks eternal. Many teenagers give up after being arrested. It’s a degrading process. The handcuffs. Patrol car. Fingerprinting. Arraignment. Noisy courtroom. Long bus ride to Rikers Island, New York City’s main penal complex. More processing. Enrollment in a new school, where it can be difficult to focus having gone through this and not knowing what the next court appearance holds.

But in the dark cloud of incarceration, education is the silver lining. Some of the finest educators in the nation work in the juvenile justice system; many see this as their life’s mission, as I do. Many innovative new teachers get their start in these hard-to-staff schools.

Nationally, rates of juveniles in residential placement have fallen steadily for more than a decade. When I first came to work as an assistant principal on Rikers Island in 1988, there were more than 20,000 inmates. Today, there are less than 8,000. The number of teenagers confined in New York City has declined proportionally.

Last October, New York State enacted legislation mandating that all 16- and 17-year-olds be moved off Rikers into Children’s Services custody. We collaborated with community advocacy groups in supporting this overdue statute and are implementing its New York City component. Students under 18 are now attending schools within youth development-oriented facilities, with access to instructional technology and positive behavioral supports. All students have a transition specialist supporting them for six months after returning home.

One former student (let’s call her Angela) left Rikers and was assigned by a judge to a residential substance abuse treatment center. She was supported by a community-based organization dedicated to advocating for young women. Upon completion of treatment, Angela began attending a high school equivalency program. She has a paid internship after school and is planning to go to college and start a business career. Angela still has the support of her Department of Education transition specialist. Her case highlights the need for interagency collaboration.

Though fewer students today are in custody, there is a greater need for mental health services, housing, and mentoring. Policies and programs focusing on prevention and early intervention should be developed, along with programs to help young parents in economic need. Extended pre-K focused on infants and toddlers provides the earliest of supports.

These program enhancements should reduce referrals to special education. When students are identified with emotional and behavioral disorders (EBD), there must be immediate, intensive supports. EBD is the number one special education category for high school dropouts and the number one category in juveniles being arrested. Intervention at the elementary school level is vital.

From elementary school onward, provisions are needed to ensure that students get to school. Mechanisms should be put in place to provide daily transport for vulnerable students. Absences often lead to grade retention. When students are left back, their chances of graduating are cut in half. Statistics show that students who have been left back twice have very little chance of graduating. Thus, we have an obligation to ensure continuity of instruction, with appropriate supports, prior to a student’s potential involvement in the juvenile justice system.

In New York, the Department of Education has piloted alternative middle schools for those who are older than other students in their grade. These programs help them catch up to their peers.

My 41 years in the New York City public school system have been focused on high schools. I always resent hearing them referred to as “dropout factories.” Education is a developmental process in which a student’s skills must advance at every grade level. When students come to high school with gaps in their learning, it is difficult to develop individual programs to meet those needs.

The first quarter of ninth grade is key. If students fall behind in the first semester, the only way they can graduate on time with their class is to make up coursework in subsequent semesters. A culturally relevant core curriculum is needed to keep ninth-graders interested. Most students do not drop out of school when they’re in 11th or 12th grade. Most arrested juveniles disengaged when they were in middle school, and a majority in this group has earned few high school credits. Educators must focus on prevention by reducing the number of students who disengage and get into trouble.

New York City has the lowest incarceration rate of all large U.S. cities, with a 53% reduction in the number of school-age inmates since 2013. Coordination between the police department, district attorneys, and other agencies has resulted in historic reductions in crime; more alternatives to detention, including treatment; and expansion of Family Court services. Fewer teenagers experiencing the degradation of arrest and confinement means fewer teens suffering hopelessness.