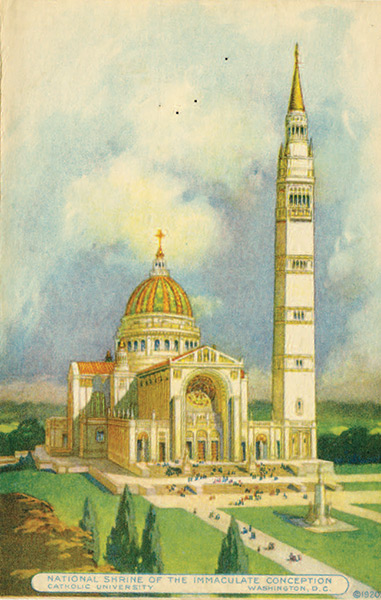

Architectural drawing of the proposed National Shrine by Maginnis and Walsh, circa 1920.

By Amanda Bernard

Sept. 23, 2020, marked 100 years since the foundation stone was laid for the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception.

It is the largest Catholic church in the United States, known to many as “America’s Catholic church.” More than one million visitors (pre-pandemic, of course) worship in and tour the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception each year.

For Catholic University students and alumni it has long been the backdrop for one-of-a-kind photo ops. It is the place they began each academic year with the Mass of the Holy Spirit, and the place where they gathered near the east steps with pomp and circumstance on their Commencement day. It’s where many performed as choir and orchestra members at the annual Christmas Concert for Charity, and where they worshipped with friends in the Crypt Church on Sunday afternoons.

It all began 100 years ago with an idea of a National Shrine and the laying of a granite block.

The 4-ton stone traveled from New Hampshire to Washington, D.C., on the back of a new-fangled green and gold “auto truck.” The brakes reportedly failed on the way through Maryland. The donor of the stone, James Joseph Sexton, remarked “how lucky we were to travel so far … without accident,” adding “I shall always reverence the Blessed Virgin Mary as I have told many … how she protected us at Perryville Road when our auto truck dashed down the hill at fully 40 miles an hour.”

Left: An unidentified laborer poses with the foundation stone on Dec.15, 1923, during the construction of the Crypt Church. Right: Cardinal James Gibbons, archbishop of Baltimore, presided over the ceremony on Sept. 23, 1920.

On Sept. 23, 1920, Cardinal James Gibbons, archbishop of Baltimore, presided over the laying of the foundation stone, as he had at numerous other occasions at the University (including the inaugural event on May 24, 1888, when the cornerstone of Caldwell Hall was laid). The next day, The Washington Post described the ceremony as “one of the most notable religious events ever witnessed in the National Capital,” and reported that “10,000 persons thronged the University campus to view the spectacle.”

Originally conceived as the University Church, the Shrine was the brainchild of Rev. Thomas Joseph Shahan, Catholic University’s fourth rector (1909–1928). Dubbed the “Rector-builder,” Shahan championed much of the campus construction in those days — from the Power Plant to Mullen Library. But the Shrine was his pride and joy. In 1913, Shahan presented his idea for a church honoring the patroness of the United States — the Blessed Virgin Mary under her title of the Immaculate Conception — to Pope Pius X, who gave Shahan his blessing along with $400.

Originally conceived as the University Church, the Shrine was the brainchild of Rev. Thomas Joseph Shahan, Catholic University’s fourth rector (1909–1928). Dubbed the “Rector-builder,” Shahan championed much of the campus construction in those days — from the Power Plant to Mullen Library. But the Shrine was his pride and joy. In 1913, Shahan presented his idea for a church honoring the patroness of the United States — the Blessed Virgin Mary under her title of the Immaculate Conception — to Pope Pius X, who gave Shahan his blessing along with $400.

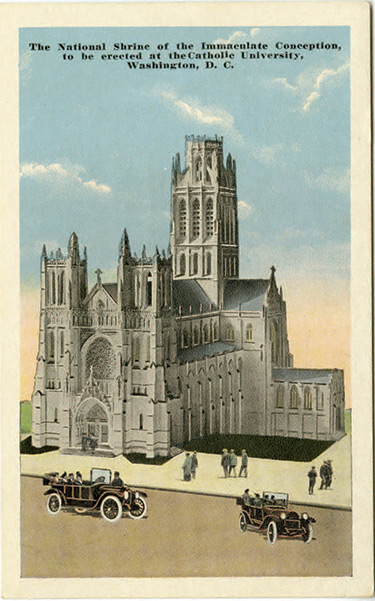

Aside from the Pope’s contribution, early fundraising efforts were dominated by Catholic laywomen — the so-called “Marys of America.” One of the most notable was Lucy Shattuck Hoffman, the mother of an established architect. In 1915, her son submitted the “plaster model of Gothic design” pictured in the early promotional materials. Ultimately, however, the University’s Board of Trustees abandoned the Gothic in favor of a Romanesque design that would echo existing Washington, D.C., landmarks.

Writing in the July 1922 issue of The Architectural Record, at a time of fierce anti-Catholic prejudice in America, Sylvester Baxter explains that, “The Shrine is by no means to be considered as intended to rival the Capitol; architecturally it complements it, rather; its grandly proportioned mass will be as manifestly ecclesiastical in motive as that of the Capitol is secular.” Similarly, the 1920 program for the laying of the foundation stone describes the height of the “noble Campanile or bell tower” as “second only to the Washington Monument.”

Construction began in 1923 and the first public Mass was held in the Crypt Church on Easter Sunday in 1924, despite the fact that it was still an active building site. The first Baccalaureate Mass was held that June — a tradition that continues to this day on the night before Commencement.

After the crypt level was completed in 1931, the project lay dormant for a variety of reasons. Rev. Shahan had resigned as University rector in 1928, but continued to oversee the Shrine project until his death in 1932 (at which time he became the first and only person to be buried within the Shrine).

Left: Laborers pose in front of the crypt level on Sept. 12, 1923. Right: Laborers pause their work for a photograph on Nov. 10, 1923. In the background sits McMahon Hall.

The loss of leadership was compounded by the onset of the Great Depression and the United States’ entry into World War II. Construction on the Shrine halted.

Back in 1924, the Salve Regina Press had predicted such delays: “When the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception will be completed is as much a problem as the great cathedral-builders of the Middle Ages faced. Business depressions, wars — many things — may intervene."

Construction resumed in 1954 and the superstructure was formally dedicated on Nov. 20, 1959. In the interim, the Shrine incorporated separately from Catholic University. Although the 1948 decision was in part financially motivated, it was mostly mission-driven; the scope of the project had simply outgrown the campus community. The two institutions have continued a neighborly relationship since.

Construction resumed in 1954 and the superstructure was formally dedicated on Nov. 20, 1959. In the interim, the Shrine incorporated separately from Catholic University. Although the 1948 decision was in part financially motivated, it was mostly mission-driven; the scope of the project had simply outgrown the campus community. The two institutions have continued a neighborly relationship since.

Although it was dedicated more than 60 years ago, construction and updates have continued in the Shrine (which was named a minor Basilica in 1990) until recent years. Construction was finally considered “complete” in 2017 with the dedication of the Trinity Dome. Catholic University students presented designs for the dome as part of a competition. At least one student was also involved in the installation of the dome through an internship.

The altar used in the Great Upper Church is also the result of a student contest. It was designed by architecture and planning students and used during the visit of Pope Francis in 2015. In addition to Pope Francis’ visit, the University community has gathered around the Basilica to greet Pope Benedict XVI and Pope John Paul II.

“It would be hard to imagine the University without the Basilica,” said University President John Garvey, whose inauguration Mass was celebrated there in January 2011. “We are fortunate to share such a strong relationship with “America’s Catholic Church” and its staff.”

While the foundation stone isn’t visible today from the outside, you can see it by visiting the Oratory of Our Lady of Antipolo within the Basilica.

Amanda Bernard is a Library and Information Science graduate student and the Archives assistant in the University Library’s Graduate Library Preprofessional Program.