Members of the Catholic University community spent a week learning about the legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the current state of racial justice in America during the MLK Teach-In in January. The weeklong series of events, discussions, and online activities was planned in place of the University's annual Martin Luther King, Jr., day of service, which could not be held this year because students were under quarantine after returning to campus for the spring semester.

Emmjolee Mendoza-Waters, associate director of campus ministry and community service, said she hoped the teach-in would be an opportunity for members of the community to reflect on the life of Dr. King and how to “become a more welcoming brother or sister, whether it be in the CatholicU community or the communities that we’re a part of.”

The teach-in was a joint effort of Campus Ministry, Athletics, Residence Life, Campus Activities, and various student organizations.

“It really is a reflection of our community and a lot of work and labor made it possible,” she said.

The keynote speaker for the week was social entrepreneur Marcus Bullock, who shared the story of his tech company Flikshop, a mobile app that helps people in prison stay connected to their community. Bullock was inspired to start the company after serving an eight-year prison sentence for a carjacking when he was 15 years old.

Bullock said that he lived in a state of disbelief for the first two years he was in prison. “The men living a few cells down from me who had much lighter skin and a worse crime had gotten shorter sentences,” he said. “I kept thinking the weekend would come and [the officials] would say they made a mistake and let me out.”

When the reality of being in prison set in, Bullock relied heavily on his mother, who would write to him every day and send photos of everything she talked about.

“She would send me pictures of hamburgers and pizzas and I’d be reading these letters thinking, ‘I can’t believe this woman wrote me a three-page letter about a slice of pizza,’” he said. “But she became the person I would have the most affectionate conversations with.”

Bullock’s bond with his mother continued as he was trying to get back on his feet after his release. Because of his felony charge, Bullock applied for 41 different jobs and was rejected by nearly every one.

“People were slamming doors in my face over and over again,” he said.

When he finally found a job as a paint mixer at a paint store, Bullock used that job as a launching pad for his own painting and construction business. After he found success, Bullock felt guilty that he didn’t have more time to connect with his friends who were still in prison. He developed the Flikshop app to enable users to send photo postcards to people in prison using their phones. Flikshop has since launched an angel program, which lets anonymous users buy credits for children of incarcerated persons so they can stay in touch more easily.

Because of his own experiences, Bullock believes in the power of listening to the stories of others, without judgement. He wants to break down the stigmas and barriers for other men and women who have served time in prison.

“One of the things I’m most excited about is changing the conversation,” he said. “We need to strip the stereotypical image of what the poster children look like for these people in these cells and to remember that they’re all human, they’re our cousins, they’re our friends.

“When we begin to lead with love and learn how to empathize, we can all begin to heal the hurt,” he said.

Later in the week, panelists discussed the relationship between race and the Catholic Church as part of a panel discussion sponsored by the School of Theology and Religious Studies. That discussion, which was part of the University’s annual Hispanic Innovators of the Faith lecture series, included panelists Michelle Gonzalez Maldonado, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Scranton, and Nichole M. Flores, assistant professor of religious studies at the University of Virginia.

Maldonado began the discussion by talking about her experiences as a daughter of Cuban immigrants who has married a Guatemalan man. She recalled a time when she and her husband got pulled over for driving a few miles over the speed limit.

“The officer took one look at my husband’s Guatemalan ID and detained him, ran an illegal background check on me, and questioned my husband on the legality of our marriage,” she said. Maldonado remembers sitting in the car and shaking.

“It did not matter that I was a U.S. citizen or that I had a Ph.D. All that mattered was that my husband was Guatemalan,” she said. “That was the most powerless I’ve ever felt and the most scared and ashamed. I worried if we made any trouble, he would be deported.”

Racism is deeply entrenched in our society and also in the Catholic Church, Maldonado said. Though the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops issued a pastoral letter against racism in 2018, Maldonado believes the Church could and should go further in acknowledging and reckoning with its past sins of racial injustice.

“Until we acknowledge our history and the original sin of racism, it’s going to remain unchecked,” she said.

Part of the challenge facing the Church when it comes to racial justice, she noted, is that “whiteness remains normative for our understanding of U.S. Catholicism even though our demographics show us otherwise.” Even though the Church is becoming more ethnically diverse each year, Latinos and other Catholics of color are still treated as special interest groups. They are also underrepresented in Catholic schools and universities.

While she was inspired by last year’s calls for racial reconciliation around the country, Maldonado shared concerns that those conversations might fall to the background in the months to come.

“If Catholics don’t understand racism as a force in direct conflict with their faith, they will never become active in the fight against racial injustice,” she said. “I hope it doesn’t take another black man or woman being killed to remind us how acute these conversations must remain.”

Flores spoke about the negative stereotypes about Latinos in the media and how these flattened representations can have a dehumanizing effect on the community as a whole. She also spoke about the need to recognize the specific gifts Latinos have contributed to the country and the Catholic Church specifically. She believes Latino communities could be instrumental in helping the Church mediate difficult challenges in the world today.

“I could spend a year talking about the ways different Latin groups have transformed devotion in the United States,” she said. “I think the Latinos are really helping us as a Church to identify some new challenges in terms of how we relate to our faith in public life.”

Both Flores and Maldonado stressed the importance of understanding the complexities of race, including how different race groups — including mixed-race groups — see themselves and relate to each other.

“While we always have to recognize the legacy of slavery in this country, that black-white paradigm is not the reality of what we’re facing in the U.S. today,” Maldonado said.

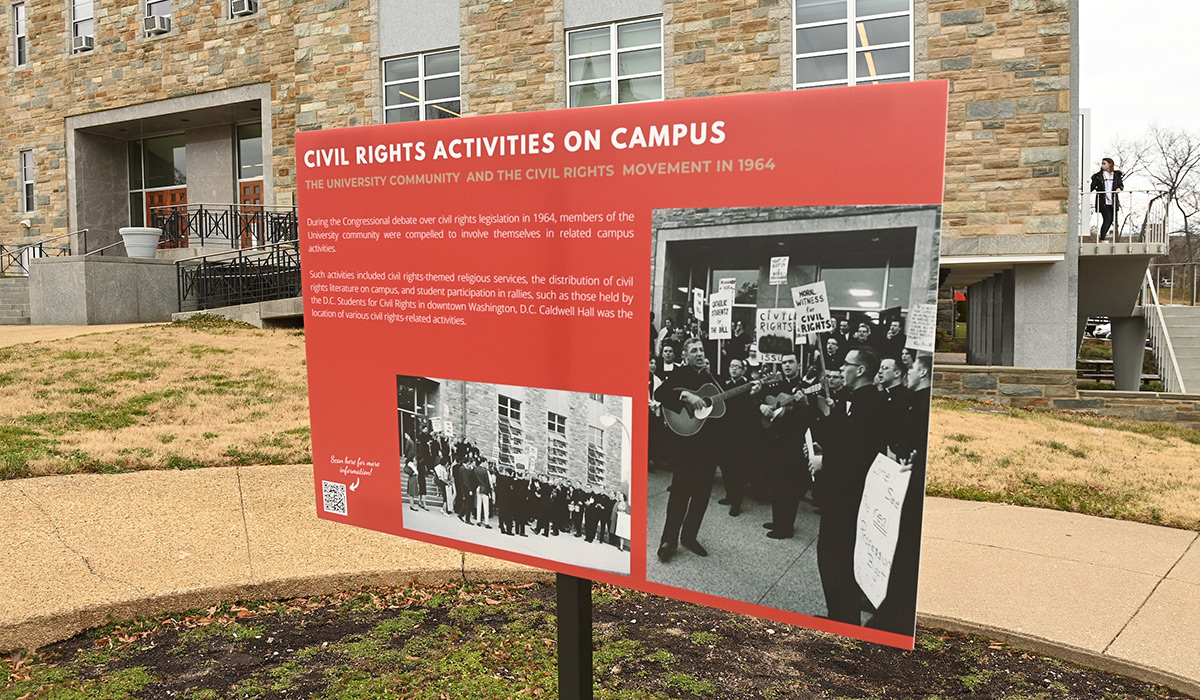

Additional events scheduled during the week included discussions on allyship and advocacy in action, a Civil Rights Walking Tour where students could learn about important people and events in CatholicU’s history of civil rights, and a virtual Mass at St. Teresa of Avila Church in Southeast, D.C.

For event recordings and a link to the Civil Rights Walking Tour, visit the MLK Teach-In website.