Eight years ago Laura Masur, assistant professor of anthropology, started her dissertation on the archaeology of American Catholics in the historical period. Through this work, she received a grant this past year funded by the Maryland Historical Trust, which allowed her to partner with St. Mary’s College to survey three different sites — a place that has been known by many archeologists in St. Inigoes, Md., called Old Chapel Field, and two other plantations, Newtown and Bohemia.

“I’m studying the Jesuits and their system of plantations that they used to fund their missions and ministry during the colonial period and into the 19th and early 20th centuries,” she said.

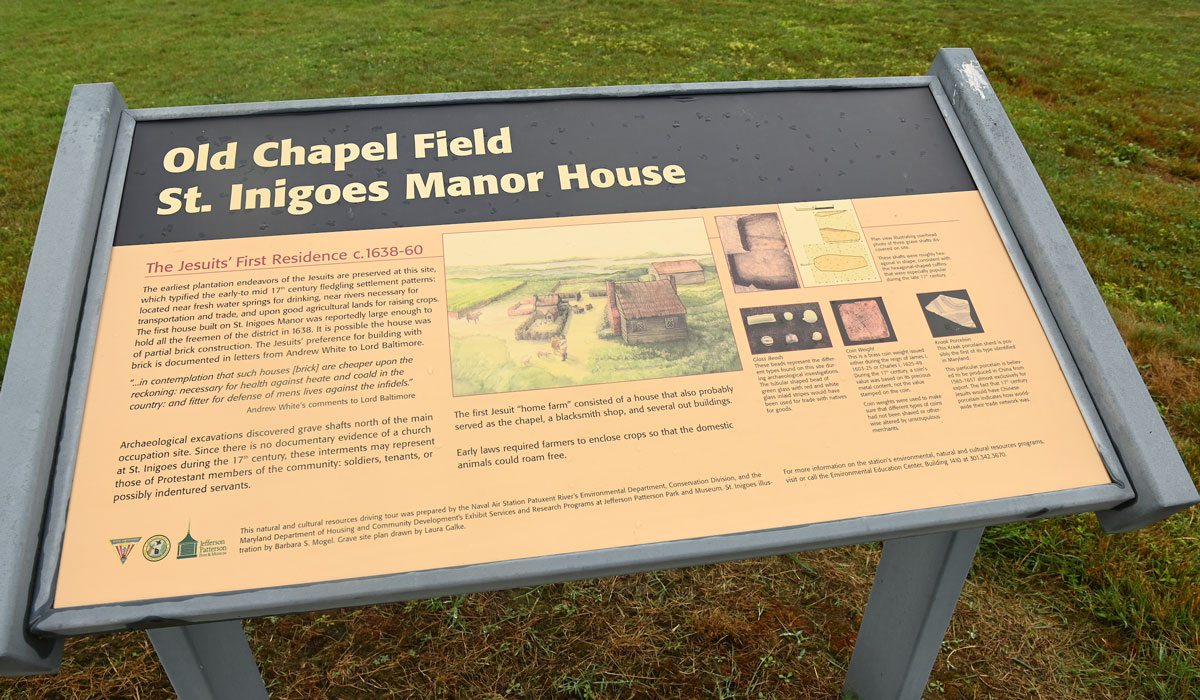

Masur was interested in researching Old Chapel Field after learning about the Jesuits and a system of their churches. She explained that Jesuits were responsible for building many of the early American churches and she found that sites in Pennsylvania were connected to sites in Maryland. Old Chapel Field is now managed by the Navy and has had many excavations there for the past 50 years.

Masur was interested in researching Old Chapel Field after learning about the Jesuits and a system of their churches. She explained that Jesuits were responsible for building many of the early American churches and she found that sites in Pennsylvania were connected to sites in Maryland. Old Chapel Field is now managed by the Navy and has had many excavations there for the past 50 years.

Masur specifically does historical archeology, working with historical documents and archeological evidence as she conducts her research. She explained that early excavations at Old Chapel Field took place during the Colonial Revival Period, the beginnings of historic preservation and archaeological research at historical sites in the United States. Old Chapel Field had eventually transitioned away from being a plantation, but was still used agriculturally by the late 1700’s. In the 1930s, “Jesuits who were studying at Georgetown would come to St. Inigoes for the summer,” she said. The Jesuits “talked to a farmer (Linwood Trossbach) who dug up bricks in Old Chapel Field. The Jesuits were interested in learning more so they pulled out shovels to dig and found more brick foundations. None of the professional surveys until now had figured out what the brick was and the theory is it’s an early church from about 1705.”

After learning more about Old Chapel Field, Masur found that previous occupants of the buildings that would have stood on the site have a large community of descendants. “Their ancestors were enslaved on these plantations, so that's a big draw for working at these sites, because they’re so important to the community of descendants as a way to connect with each other and places through these sites.”

For this project Masur has been working with a professor from St. Mary’s College, field technicians, descendants living in the area, and CatholicU students, who have the opportunity to get first-hand experience in the field.

They’ll spend about seven weeks in the fields before starting the planning and processing of artifacts in the lab on campus, where students will get to wash, catalog, and write up reports on artifacts they’ve found.

“The real work of trying to tell stories starts in the lab. This is where you think about the connections between the sites, people, and objects,” Masur said. “A lot of the time you don’t understand what you’re seeing until you can map everything out, look at the data, and start to understand and connect everything.”

Maria Letizia, a rising senior with a double major in history and anthropology, has been involved in the project by working in Bohemia on the Eastern Shore doing shovel test surveys.

“We began by creating a graph map where we would plant a flag every 25 feet in order to dig test pits and establish an idea of what lies below the ground before opening up bigger test pits. Once we dug a test pit, we sifted all of the dirt by soil layer to make sure we would find all of the artifacts that could possibly be there. Once we are done with a hole, we need to do paperwork in order to properly document what came out of the hole as well as the soil type and the munsell count (A color system to visually identify and match color using a scientific approach),” Letizia said. “The experience so far is something I have never done before and have really enjoyed. The fieldwork is hard but finding artifacts is gratifying, even after a long day of digging in the sun. I am grateful to Dr. Masur for allowing me to aid in her research and be provided with this field experience.”

“After being in the field we did find evidence consistent with the presence of a church — the artifacts are very similar to what was found when the 1666/7 church was excavated at Historic St. Mary's City in the 1990s. But we'd really need to return to the site in the future in order to confirm this theory,” said Masur.

“However, I’m most excited not so much about what I find. It’s about having descendants be involved in the project and to be able to tell stories about the site. There are very few records and stories of people who were enslaved there. This project is a way of facilitating connections to places or parts of history that get overshadowed.”