On a starlit stage, an old woman rocks in a chair. She is weeping. Gradually, dancers join her, as off-stage voices sing a hymn: “Blessed quietness, holy quietness, Blest assurance in my soul. On the stormy sea, Jesus speaks to me, And the billows cease to roll.”

More dancers enter and begin to move together, lifting each other up, and then drifting apart. Soon it becomes clear they are playing a single role: They are a river.

The dancers play a crucial part in Lindsay Adams’s play, River Like Sin, which premiered on the Hartke stage in February. As the play progresses, they are a constant presence, either leaping and tumbling to represent high water or lying limply to symbolize drought.

The river is the invention of Adams, an M.F.A. playwriting candidate in the Department of Drama, who was inspired by her memories of growing up in rural Arkansas.

“I spent a lot of my time wandering through creeks, ferns, and gullies,” said Adams, who now lives in Kansas City, Mo. “There are really beautiful things about living in a small town.”

Adams’s play is a reflection of her love for the American Midwest and the culture shock she felt after moving to Washington, D.C., for graduate school.

“Especially after the [2016] election, I kept having these interesting conversations in class about the people living in the Midwest, like ‘Who are those people?’” Adams said. “I realized I needed to be writing about that. I have the ability and experience to talk about these people because I love them and I know them.”

Adams also drew inspiration from the world of folktales and magical realism.

“I always loved the way we use story and narrative to deal with actual things that are happening,” she said. “I wanted to do a folktale adaptation, and I had this image in my head of a woman in a rocking chair crying and her tears falling into the river as it grows faster and fatter. It stuck with me and I thought, ‘What if she stopped crying and the river dried up? What would happen then?’”

Adams believes theatre offers writers a unique opportunity to deliver stories directly to an audience that is open and engaged.

“I realized that when you write a play, you get to play all the characters yourself. You have an understanding of the whole thing.”

“I love that idea of people all being in a room together, experiencing something that is happening right in front of them,” Adams said. “The level of connection and empathy in that experience is huge.”

Helping writers like Adams tell their unique stories is a specialty of Associate Professor Jon Klein, who is director of Catholic University’s playwriting master’s program. Since joining the University in 2004, Klein has helped to train playwrights from around the country.

“Some of my students have come straight out of college, and some have bounced around for a while,” he said. “Some of them are looking for experience writing, while others are more geared toward teaching.”

Klein’s students have written in every conceivable genre from satire to surrealism, deep fantasy to dark comedy. The one thing he thinks they have in common? “They all have interesting stories to tell.”

Though it might seem similar to writing poetry or fiction, playwriting is a unique art all its own. A play’s distinguishing element is that it is meant to be performed, brought to action in front of a live audience.

“If you’re writing a novel, you might assume someone is reading it, but you don’t usually meet them,” Klein said. “Here, you’re in a theatre with 200 or 500 people and you can tell if they like it or hate it in real time. I’ve known people who started out as poets and novelists, but they became playwrights and never looked back.”

Like many others, Klein was drawn to the world of playwriting after first trying his hand at acting. “If you’re a good actor, you begin to realize your own limitations. I learned that I was pretty good, but that I was only going to go so far,” he said. “I realized that when you write a play, you get to play all the characters yourself. You have an understanding of the whole thing.”

Since then, Klein has written dramas and comedies, musicals, absurdist theatre, and theatre for young artists. As a “working-stiff playwright,” he has had more than 30 plays produced all over the country and won numerous awards. He also wrote a book on his experiences, titled Life as a Playwright: A Survival Guide, published by Methuen Bloomsbury in May.

This spring, Klein was honored with the University Provost’s Award for Achievement in the Creative Arts. In his current role, Klein leads students through a rigorous lineup of writing classes and classes on other topics taught by drama faculty. The writing classes are purposefully small and, historically, the M.F.A. playwrights have been fully funded by Catholic University scholarships, enabling students to dedicate three years to their craft without incurring debt.

The hallmark of the program, Klein said, is that each student has a thesis play produced as part of the Hartke mainstage season. These productions are cast with student actors and directed by working professionals in the D.C. theatre scene.

“That’s one of the main reasons people come here,” Klein said. “They work with set designers and the director and they get a sense of what it’s like to be produced as a playwright,” Selecting students for the program, Klein always keeps that final production in mind. He looks for students with writing styles that are completely their own.

“I don’t help them find their voice. My job is to help them realize the strength of their own voice,” he said. “I always ask, ‘What kind of play do you want to write? Let’s make that kind of play as good as we can.’”

Playwriting candidate Liz Maestri enrolled in the program when she was in her early 30s. After earning a bachelor’s degree in theatre from the University of Maryland in 2003, she had moved to New York to pursue an acting career. It was there that she got to know a group of playwrights who wrote with a raw boldness she hadn’t seen before.

“I began to get really interested in what they were doing,” she said. “I wanted to find my own voice and use it to affect people in ways that only writing can.”

After moving back to D.C., Maestri became involved with the Taffety Punk Theatre Company, an ensemble with a mission of making theatre accessible for new audiences. There, she submitted her first play, Owl Moon, for a production in 2011. The experience was thrilling.

Since then, Maestri has been reaching for opportunities anywhere she can find them. She applied to the master’s program as a way to devote herself to playwriting. At the time, Maestri was working as a project manager for the Public Broadcasting Corporation.

“I was at an age where it felt like a real fork in the road, and I was asking myself, ‘What are you going to spend your life doing?’” Maestri said. “I realized I didn’t want to spend mine in an office.”

A self-proclaimed feminist writer, Maestri likes to write about her life or things that are bothering her. Many of her plays have strong female leads and deal with issues related to violence or the patriarchy.

For her thesis play, The Knot, Maestri drew inspiration from her experiences after getting engaged in 2016. Though she had never cared much about weddings, Maestri suddenly found herself sucked into what felt like a bridal industrial complex. She was overwhelmed with long lists of expectations people had for her as a bride.

“The play is where I could take some of that anxiety and make something out of it, because I know I was not alone in that unease,” she said.

Eventually her play became a dark comedy skewering the consumerist nature of weddings and gender roles, including the “Disney princess” expectations for brides. Maestri’s story is about a fairy-tale princess who comes to Earth to convince Khymi, a spin instructor living in D.C., to become the best bride she can be. As Khymi loses herself in her goal, she also loses sight of the things that matter most, including her career and her relationship. Working on the play presented Maestri with the challenge of figuring out how to portray castles, spin classes, and even a condensed wedding reception on stage. The thesis production, she found, gave her room to experiment.

“You’re not trying to sell tickets and you’re not trying to get good reviews,” she said. “And it’s been great to have the ability to keep working. I’ve been doing rewrites throughout the whole process and having that freedom is really cool.”

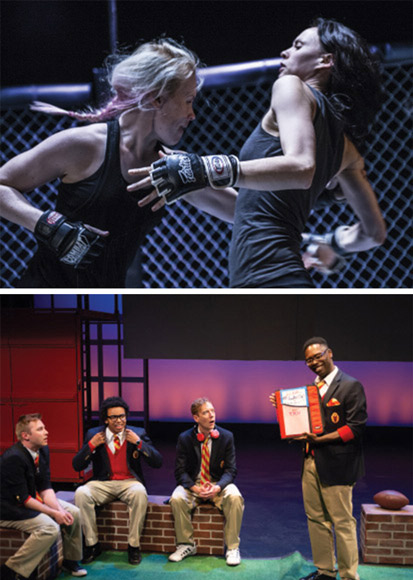

– Teresa Castracane, Meridith DeAvila Khan/Sweet Briar College

– Christopher Banks, courtesy of Mosaic Theater Company

Though playwriting is his passion, Klein doesn’t pull any punches while telling his students about their job prospects. While he believes there’s a “hunger for new writing” in every genre, he admits that playwriting is not an easy path.

“It can be a tough life and you have to do it for the love of theatre,” he said. “It’s hard to make a living from writing plays, for even the most famous playwrights. They might be lucky enough to work in TV and film, but they almost always would prefer to write for theatre.”

That said, numerous alumni of the program are proving that it can be done. According to Klein, 2018 will bring a record number of professional productions by various alumni of the program. Some, including Kathleen Jones, M.F.A. 2015, have taken measures into their own hands.

Jones, an actress and playwright, lives in New York with her husband, Orion Jones, who earned his M.F.A. in directing from Catholic in 2015. A few years ago, she began collaborating with acting alumna Amie Cazel, M.F.A. 2015, to produce plays under the name Good Pilgrim.

The pair’s first play, Pregnant Pause, depicts 45 minutes in the life of an actress who finds out she is pregnant on the same day she learns she has been cast in her first Broadway role. A collaboration between anti-abortion and abortion rights women theatre artists, the play depicts a woman’s feelings about sex, pregnancy, abortion, and her career as she grapples to make a decision about which path to pursue.

In the end, the play doesn’t reveal how the main character responds to her pregnancy. The point, Jones explains, is to build empathy for the difficult decisions women face.

“We’re focused on showing this one woman and what she goes through, what she feels, and all the ugly stuff she doesn’t want to admit to feeling but does,” Jones said. “We’re really proud of it, and we’ve received good responses from a lot of people on both sides of the abortion debate.”

Increasing empathy through theatre is a big motivation for Jones. Because she has cystic fibrosis, a genetic lung disease, she often incorporates themes of illness into her work. As a Catholic, she often includes questions of faith as well. Her latest collaboration with Cazel is a web series telling the story of a millenial woman who is discerning a call to the religious life.

“In the show, she gets dumped by her boyfriend for the seminary and then she has to figure out on her own what she is going to do,” Jones said. “It’s very funny.”

Several playwriting alumni have gone on to receive major accolades for their writing. Playwright Stephen Spotswood, M.F.A. 2009, now teaching in Washington, D.C., received Helen Hayes awards for outstanding original play and outstanding choreography in 2017 for his play Girl in the Red Corner, about a female mixed martial arts fighter. Spotswood said he has has fond memories from his time studying at Catholic University, where he learned how to experiment and collaborate creatively. Spotswood loved squeezing as many elements as he could into his thesis play, Miranda is Morning, including a drag show, a journey into the underworld, a ghostly circus, and a country-western dance routine.

“Basically I was having fun finding ways to manifest the impossible on stage,” he said. “The program really stressed the importance of collaboration in the rehearsal room, and my thesis was my first shot at really test-driving everything I had learned.”

Today, Spotswood continues to write as a member of the Welders playwrights’ collective alongside fellow Catholic University alumna Annalisa Dias, M.F.A. 2015. Many of his plays deal with women struggling to “find a place in a world that’s stacked against them” or issues of class and family expectations. He credits his Helen Hayes awards, in part, to his many collaborators.

“By working with a group of actors and designers and a director and everyone else involved in a production, I get to create a work of art that goes far beyond my own experience and abilities,” he said. “Every artist involved in a show adds their own perspective and talent.”

Tearrance Arvelle Chisholm, M.F.A. 2016, is another alumnus who has gone on to achieve great things. This May, he was awarded the Helen Hayes award for outstanding original play for his work, Hooded, or Being Black for Dummies, which he wrote at Catholic University. The play made its debut at D.C.’s Mosaic Theater Company last summer. After receiving rave reviews, it was remounted this Spring.

While at Catholic University, Chisholm said he learned to be flexible within a “healthy set of limitations.”

Through dramaturgy and theatre history classes, he learned the established rules and guidelines for playwriting. He also learned the ways in which he could subvert the rules and chart a path for himself.

For his thesis play, Chisholm wrote B’rer Cotton, about a 14-year-old boy living with his family in a poor neighborhood on land that was once a successful cotton mill. As the boy learns more about the violence black Americans face in society, he becomes more overwhelmed and enraged, eventually leading to a rift between him and his family members.

After its debut in Hartke, B’rer Cotton was accepted into the National New Play Network and performed in several cities around the world over the course of a year, including Dallas, Los Angeles, Cleveland, and London. Chisholm, who is now enrolled in a postgraduate program at Julliard in New York, said he was inspired to write both B’rer Cotton and Hooded as a response of the killings of black men like Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown. As one of a few black students in the Department of Drama at the time, he felt a need to make his voice heard.

“I used feelings that I was having because I was a minority and the only black man in the building,” he said. “I had a real sense of urgency at that time to talk about my feelings about race.”

In his latest writing, Chisholm said he is less interested in racism and more interested in representation. One recent project is P.Y.G. or the Mis-Edumacation of Dorian Belle, a retelling of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion, in which a white Canadian singer seeks the help of Chicago rappers in order to increase his pop music standings. The play will be produced by Studio Theatre next year, with Chisholm as director.

When he’s stuck on a particular piece of writing, Chisholm said he always remembers the advice he once heard from the famed American playwright Lynn Nottage. “Her advice is to ‘Just tell the truth,’ and I think that has really registered with me,” Chisholm said. “Whenever I get lost while I’m writing and I’m not quite sure where to go, I always try to think about the truth of the situation and telling my personal truth. That has never steered me wrong.”