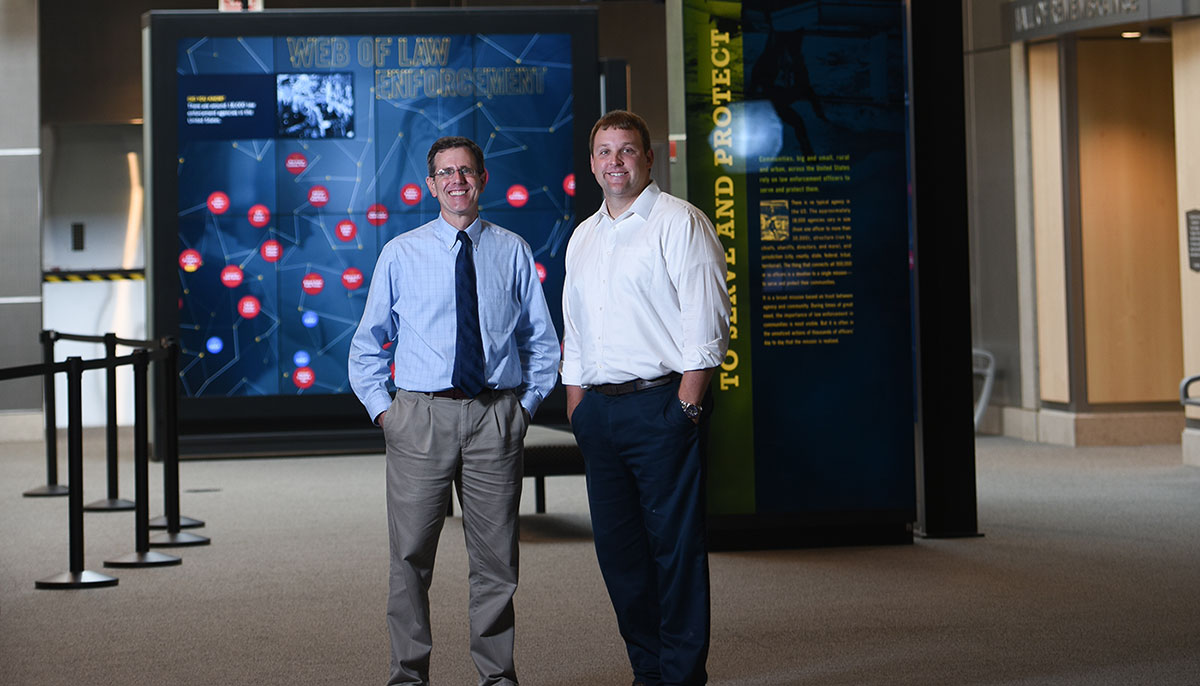

An architecture alumnus and an engineering alumnus led the design and construction of D.C.’s newest museum.

Tom Striegel, B.S.Arch. 1984, B.Arch. 1985, is the vice president of Davis Buckley Architects and Planners; Mike Geraghty, B.C.E 2008, is a senior project manager with Clark Construction. When construction began on D.C.’s newest museum in 2016, they became colleagues and friends.

The National Law Enforcement Museum opened to the public in October at Judiciary Square. Striegel was the museum’s lead architect. Geraghty was the senior project manager. The museum is a project 20 years in the making. In 1998, Striegel and his team at Davis Buckley were called in by the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund as the group began fundraising and planning. In 2000, the museum was officially authorized by an act of Congress. Geraghty set up shop at the construction site in April 2016 when Clark Construction began the 70-foot excavation at the site on E Street, N.W.

Striegel and Geraghty had a difficult design and construction challenge ahead of them. The land was deeded to the museum with a number of restrictions in order to maintain the visual impact of Judiciary Square. Directly across from the museum property is the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial, a three-acre park dedicated to law enforcement officers who died in the line of duty. Striegel was part of the Davis Buckley team that designed the tree-filled memorial.

Across F Street at the north end of the memorial is the National Building Museum, and across E Street to the south is the District of Columbia Court of Appeals.

“One of the most important restrictions in designing the museum building was that we could not block the visual axis from the Building Museum, through the memorial to the Court of Appeals,” says Striegel. The solution? The museum is largely underground.

“We set out to design structures that would keep the open feel of the square and that would allow natural light into the museum,” says Striegel. “We felt it was critical that museum visitors didn’t feel like they were going down into a dark Metro station.”

The architects designed two glass pavilions, 100 feet apart — one for entry and one for exit. “At the highest point each pavilion is 25 feet, but to reduce their visual mass and have them sit comfortably amid the court buildings, the tops are curved, bringing the lowest point to 16 feet around the perimeter,” says Stiegel.

The glass pavilions were fabricated and pre-assembled in Europe by a German company known for intricate custom designs. They were then taken apart and shipped to the museum. “I tell people these are the biggest, most expensive LEGO sets you will ever find,” says Geraghty, who made a few trips to Europe with Striegel and other members of the design and constructions teams to supervise the production of the glass structures.

Once the concrete structure of the underground building was in place, the engineers had to plan well in advance for materials that would have to come in before the building was complete. “With this being underground, anything that wasn’t going to fit on the service elevator had to go in first,” says Geraghty. “The biggest pieces to go in early were the escalators and grand staircases.”

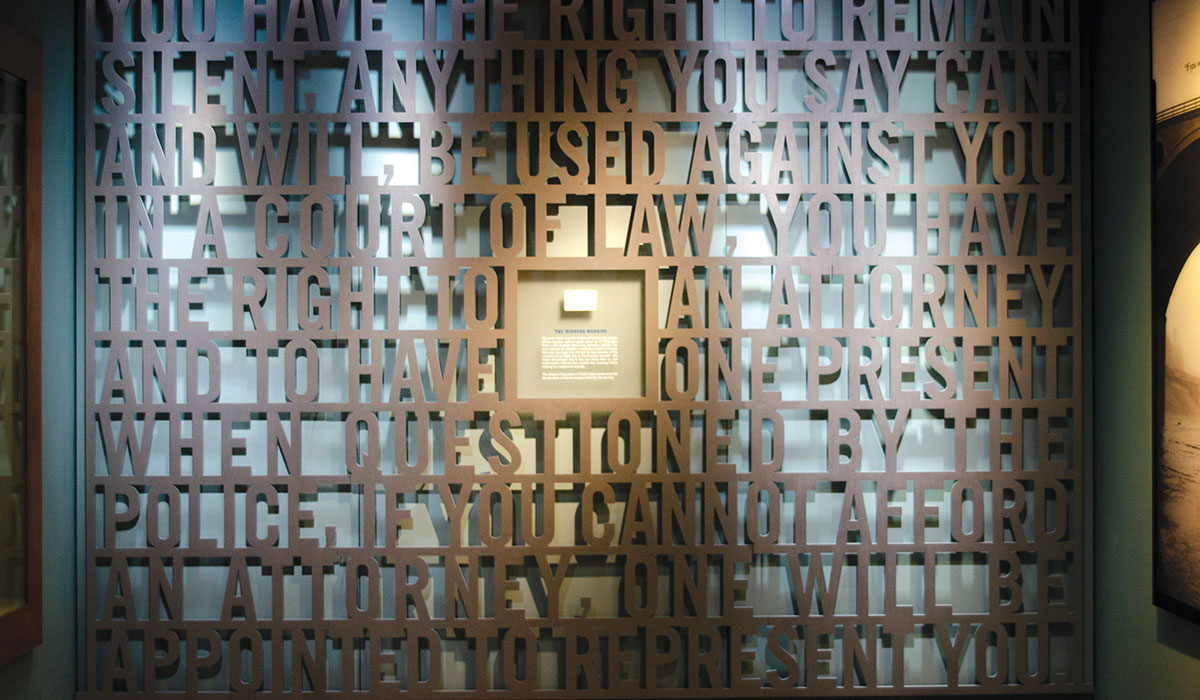

“We had to work closely with exhibit designers and curators to bring their exhibits to life,” says Striegel. “They envisioned a museum where citizens would have a chance to walk in the shoes of law enforcement officers. They wanted a visit to this museum to be about experiences.”

Interactive exhibits allow visitors to “take” a 911 call, ride along with officers, make split-second life-and-death decisions in a training simulator, and solve crimes.

The museum does not shy away from negative law enforcement stories in the news. Headlines from the Michael Brown shooting in Ferguson, Mo., are featured in one exhibit.

Beyond the exhibits, museum leaders have launched a pilot affinity project with Prince George’s County, Md., bringing together citizens, community leaders, and the police department.

“I feel connected to the museum’s mission and grateful to play a role in something that will help citizens appreciate law enforcement,” says Striegel.

When Geraghty learned he would be the project manager for the museum, he thought of his late grandfather, William Geraghty, who was the deputy chief of police in Newark, N.J.

On the mezzanine level of the museum overlooking the exhibit floor is a glass railing that contains a “Thin Blue Line” of inscriptions. Geraghty made a donation and added his grandfather’s name to the railing.

“That’s the great thing about building a museum — you are preserving history,” says Geraghty. “I’m just happy I got to be part of it.”

The story is an excerpt of a feature article that appeared in the fall 2018 issue of CatholicU Magazine. Read the full article on the CatholicU Magazine website.

Photos in slideshow courtesy of the National Law Enforcement Museum