By Mariana Barillas

This year’s forecast: Sunny with a chance of solar storms. As the sun enters a “solar maximum” phase, an active period that it enters every 11 years, space weather is a hot topic.

Meteorologists can tell us if it’s going to rain or snow, but their knowledge base is largely limited to below the stratosphere. Space weather researchers examine variations in the space environment around the Earth, extending from the sun to the upper layers of our atmosphere.

Solar storms, or bursts of electromagnetic energy, can send shockwaves through the solar system. They can cause stunning lower-than-usual aurora borealis but can also wreak havoc on staples of modern life, including satellites, cell phone service, the internet, and GPS. Back in 2003, the northern lights reached as far south as Australia, astronauts in the International Space Station took cover, and communication problems disrupted commercial flight operations.

The sun continuously emits energy, so there’s always another event of varying intensity on the horizon. That we seldom notice a solar storm underway is thanks in large part to researchers and innovators focused on space weather.

The Catholic University of America is a leading institution at one of the largest, if not the largest, hubs for heliophysics research in the world. In 2021, the University received $64.1 million — the largest grant in University history — from NASA to lead PHaSER (Partnership for Heliophysics and Space Environment Research). This cooperative agreement with five other higher education institutions supports the agency’s heliophysics division at Goddard Space Flight Center, one of NASA’s major centers for space science and exploration in nearby Greenbelt, Maryland.

About 100 space weather scientists who drive discovery in the division are University employees — and this number doesn’t include researchers in PHaSER’s sister cooperative CREST II (Center for Research and Exploration in Space Science) and many other alumni who work at Goddard.

Physics Research Professor Robert Robinson, who leads PHaSER as its principal investigator, explained the rise in visibility of space weather has to do with society’s increasing reliance on technologies, especially in communications, which are sensitive to solar events.

He said interest is “blossoming,” especially among the next generation. Space weather is an emerging and evolving field, offering ample opportunities to boldly go where no researcher has gone before.

“Young people and students are excited to make a difference and be pioneers,” he said.

Director of the Moon to Mars Space Weather Analysis Office Yaireska “Yari” Collado-Vega, Ph.D. 2013, in the team’s headquarters.

Cardinal community members are crucial contributors to many of NASA’s highest-profile projects, including the Artemis program that aims to send humans back to the moon as soon as 2025 and will lay the foundation for a future mission to Mars.

“There’s never been a better time to study space weather,” said Yaireska “Yari” Collado-Vega, Ph.D. 2013. She directs the Moon to Mars (M2M) Space Weather Analysis Office, the only NASA space weather analysis and forecasting group with a scope that extends beyond the region between the Earth and the sun to reach into deep space as far as Jupiter.

The nine-person team, seven of whom are University-employed analysts and researchers, is a proving ground for emerging real-time analysis techniques and supports the development of improved computer models for predicting the space radiation environment.

It’s a big job because the sun’s explosive temperament is notoriously hard to predict.

“Right now, the amount of warning we might have can be as little as ten minutes,” said Collado-Vega. Their goal is to collect as much information as possible to help move the needle on lead time for future Artemis astronauts to take cover in their ship or on the moon’s surface to protect themselves from the radiation environment.

Failure isn’t an option, so the sun never sets on the Moon to Mars (M2M) Office. They work in shifts, monitoring the sun every day (including holidays). In the leadup to the Artemis missions, they have provided 24/7 mission-critical support for some of NASA’s highest-profile projects including the 2021 James Webb Space Telescope launch.

This careful monitoring is essential because even a small solar event can cause major impacts. When a minor geomagnetic storm hit the Earth’s atmosphere during a 2022 SpaceX launch and nearly 40 brand-new satellites began falling from the sky, Collado-Vega was on speed-dial and provided an assessment to NASA’s headquarters.

“In less than an hour, I sent a whole summary of everything that was happening — the flare, the coronal mass ejections, how they arrived, what happened upon their arrival — everything,” she said. The catastrophe brought new visibility to space weather and led to an industry-wide effort to build better collaboration among agencies and private enterprises.

For the M2M team, it’s all in a day’s work.

Each morning begins with an all-team meeting, where they gather in front of a big screen to share their analysis of the most recent solar activity with representatives from across the agency and from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Space Weather Prediction Center, the country’s official source for space weather alerts and warnings. This “tag-up” is usually in the “WOW” room that gets its name because that’s the first thing people say when they step inside and see the 180-degree floor-to-ceiling big screen. Today, it’s in a shared workspace that feels less like an office and more like a situation room.

Usually, these morning meetings last no more than 5–10 minutes. With the sun more active, it’s more common for them to extend to as much as half an hour. And overnight, the sun was especially busy.

“You came on a great day,” said M2M deputy director Michelangelo “Michel” Romano, B.S. 2015, as he marveled at time-lapsed videos of last night’s stunning and gargantuan explosions that travel hundreds of miles per second. Thankfully, Earth’s magnetic field shields us from its worst effects and makes life on our planet possible.

It’s times like these when Romano thinks about the glory of God’s creation. He chose to study at the University because he wanted to delve deeper into both his Catholic faith and space science.

“I love diving into the physics of something that is dynamic, chaotic, and complex to appreciate the order and structure that comes not just from somewhere but from Someone,” said Romano, a message he instills in the three children he is raising with his wife Patricia, B.S. 2015, whom he met when they were both studying physics.

Romano said he got his first internship at NASA Goddard, thanks to faculty investment in student success and the connections forged on campus. He said the small class sizes made him “feel like more than a number,” and the University is a “great pipeline” to Goddard, especially with the launch of space weather academic concentrations since he graduated.

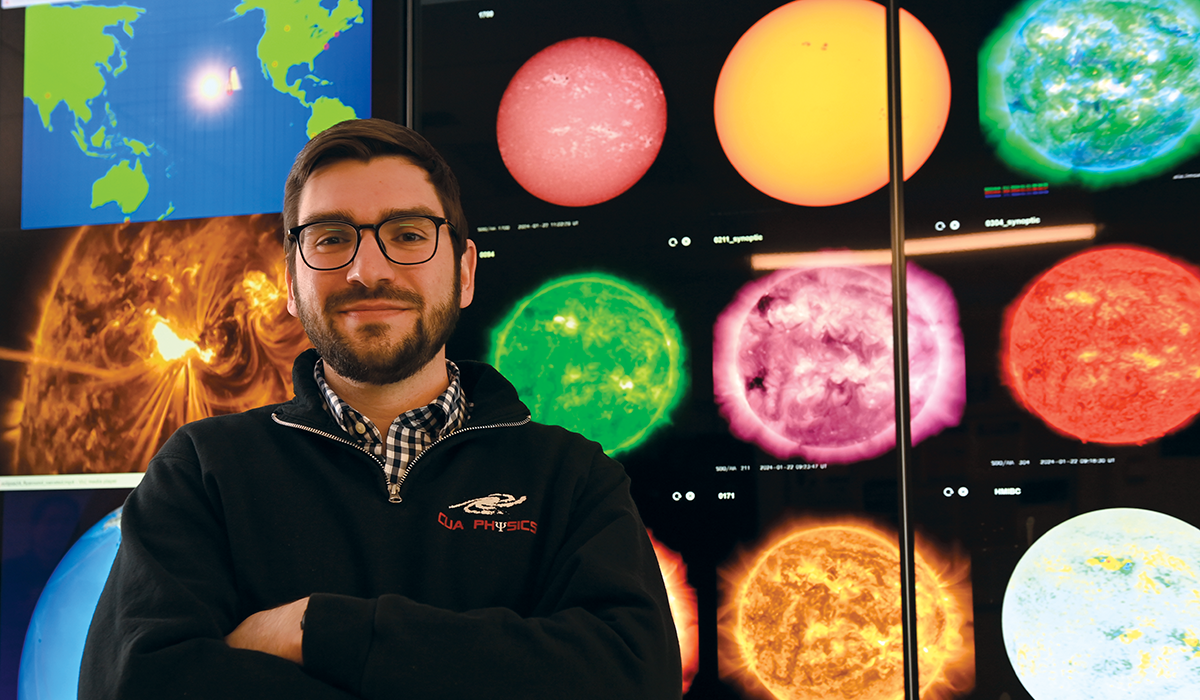

Associate Professor of Physics Vadim Uritsky teaching at the University’s Space Weather Center, an on-campus lab where students can study space weather events in real-time and learn forecasting skills.

The University is an innovator in training the future generation of space weather researchers, offering a rare minor available to any undergraduate, regardless of major. The Master of Science in Applied Space Weather Research is the first degree of its type and Robinson’s brainchild.

He explained that space weather is rarely a standalone course of study at most universities but is typically spread out among different disciplines such as meteorology, physics, and electrical engineering. Robinson saw a need for a program that put all the pieces together. He also believed it needed to be much more than “research for research’s sake.”

“To really understand the full impact of a space weather event, you need people with a lot of different expertise,” said Robinson. “We try to give the students a multidisciplinary view of the knowledge they need to tackle this problem.”

The undergraduate and graduate curricula combine several branches of physics with skill development in observation techniques including data mining and computerized forecasting methods. The courses are taught by University faculty, PHaSER researchers, and NASA civil-servant scientists.

The master’s degree program director and Associate Professor of Physics Vadim Uritsky said there is high demand in a wide variety of industries because of the threat solar events pose to critical civilian infrastructure, both in space and on the ground. He said the “solar maximum” is uncharted territory for a lot of new technologies, such as driverless cars, that did not exist the last time the sun was this active.

One of the program’s first graduates, Samantha Carlson, M.S. 2022, manages the Federal Aviation Administration’s newly established space weather-specific research program, where she works to build upon the agency’s knowledge base. It’s important especially for flights that go over the Earth’s poles — regions where the impact of space weather is more pronounced — because they sometimes need to be rerouted or canceled to avoid exposure to an event.

“We’re looking at space weather’s effects, what are our strengths and what are our weaknesses … It’s about determining what’s already in place to combat issues and staying ahead of the game,” said Carlson, who credits her fast-track into the field to the faculty’s fostering a learning environment for students to pursue their individual interests.

The number of students pursuing the master’s degree is a handful a year but is growing along with the discipline’s visibility. Physics Research Associate Professor Dr. Gang Kai Poh, who is also a researcher at Goddard, said this year the program reached its highest ever enrollment.

He said a big focus for the program this year is the April 8 total solar eclipse, which will be the last visible event in the United States for the next 20 years. His students built sensors that will be deployed along the path of totality, where the moon completely blocks the sun, to detect changes in the Earth’s magnetosphere during the event. The data will be submitted to NASA for analysis.

For Poh and his colleagues, creating opportunities like these and inviting leading scientists from across the country to class to speak with students is all part of building the University into a hub for innovation.

“The whole idea of this degree program is to train the students so they can join industry, academia, or NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center as forecasters to be leaders in their field,” said Poh.

For space weather science at the University, the future’s looking bright.