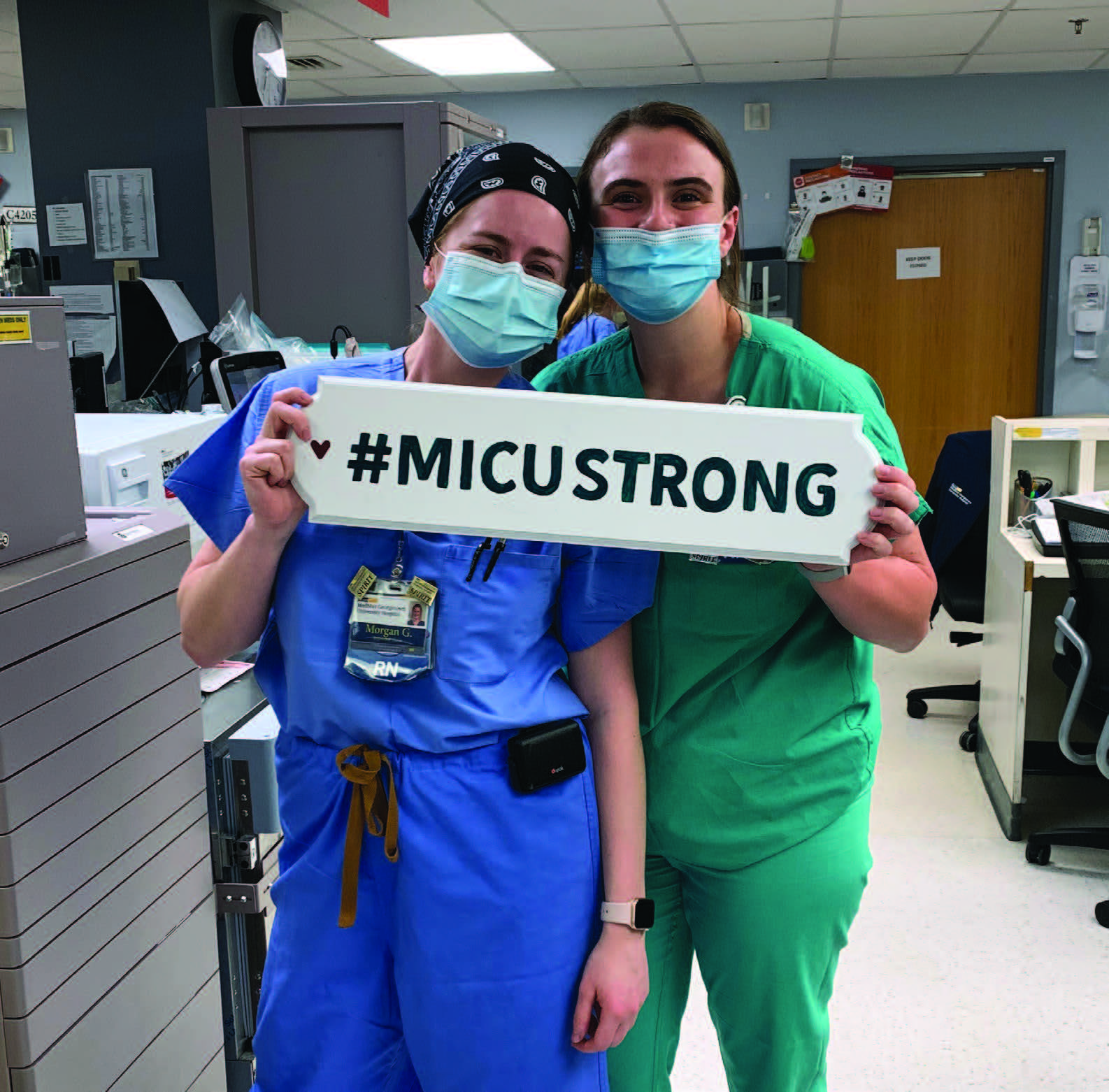

Morgan Gluck, B.S.N. 2017, at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital.

By Catherine Lee

CatholicU Magazine, Summer 2020

Three CatholicU nurses detail the challenges, sadness, and triumph of caring for patients as the COVID-19 pandemic hit the U.S.

Ally Marcello knew her patient, a man in his mid-60s, probably wouldn’t live to the end of her shift. He was on a ventilator, getting 300 milliliters of vasopressors — known as “pressors” — an extremely high dose of medications to tighten blood vessels and elevate blood pressure. But he was still crashing.

As Marcello was FaceTiming with the patient’s children, the line on his heart monitor suddenly went flat and she had to tell them that he had died. She held it together as they said their goodbyes. But when they hung up, she collapsed on the floor crying.

After weeks of caring for patients at Northwell Health Long Island Jewish Medical Center who were dying without their families, the stress and sadness were too much. Marcello, B.S.N. 2018, said getting to sleep after that shift was hard, but she was back on her COVID unit the next night.

Nothing could have prepared her for the unique challenges of caring for patients with COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus. But the Conway School of Nursing gave her the foundation she needed to adapt, acquire new skills, and develop the emotional stamina to do the job five nights in a row for weeks on end.

Early last March, Marcello knew little about COVID-19. By early April, when New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo identified the medical center and five other Long Island hospitals as hot spots for COVID cases, Marcello had seen plenty of it. Intubation was commonplace. Code blues were routine. By May, 500 patients at the center had died of COVID-19.

As the number of cases surged, the medical center started turning its ICUs into COVID units. The hospital — one of the largest on Long Island — was admitting patients from other New York boroughs. Initially, hospitals were seeing patients with fever, cough, shortness of breath, fatigue, headache, and muscle aches. Over time, the list of symptoms grew to include kidney and liver failure.

“We had no idea what we were up against,” said Marcello. “It seemed like all our patients were deteriorating or dying. It was really scary.”

In the surgical ICU where she worked prior to the pandemic, Marcello cared for two patients at a time. In the COVID units, she was caring for four at a time in a negative pressure room, which prevents airborne diseases from escaping and infecting other people.

Last December, Marcello started making what she called ISeeU Blankets for families of patients who had died in her surgical ICU. As the number of COVID-related deaths started rising, another nurse joined the effort. By late May, they were putting together sympathy bags that included a blanket, a candle, and a packet of forget-me-not seeds. If they had a patient’s fingerprints and EKG strip, they would frame those and add them to the bags.

When a COVID patient dies, one of the nurses calls the next of kin and asks if they’d like to have a bag. Sometimes the nurses make several deliveries a day, notifying a family member that they’ve left a bag outside their house, waiting for them to answer the door, and then slipping away.

Marcello said she hopes the bags help to alleviate the families’ pain of not being with their loved ones when they passed away. “Putting together the frames is sad, but I feel better knowing families are getting a remembrance of their loved one. Maybe it puts a smile on their faces.”

At MedStar Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, D.C., the palliative care team gave Morgan Gluck, B.S.N. 2017, and her fellow nurses two wreaths made of braided branches and a batch of silk ribbons in different colors. When a COVID patient dies, that patient’s nurse ties a ribbon on a wreath.

“It’s kind of bleak that each ribbon represents a death, but each one also represents a person,” said Gluck. “For me, it’s kind of therapeutic. I can say ‘I cared for that patient.’”

When MedStar Georgetown started admitting COVID patients in March, there was little reason for hope. In an email to Jane Taylor, clinical professor of nursing and Conway School faculty mentor, Gluck wrote of “an underlying sense of impending doom … we’re calling it pre-traumatic stress. We stand ready to fight, preparing for the worst, and hoping/praying it doesn’t come to that point.”

Gluck, who lives in D.C.’s Columbia Heights neighborhood, was working in the hospital’s medical ICU prior to the pandemic. She had worked on the unit as a Conway Scholar (a nursing scholarship program funded by University benefactors Bill and Joanne Conway) the summer before her senior year. After graduation, she was hired full time and assigned to the same unit.

Patients on the unit had a range of issues, including acute respiratory distress syndrome, multi-system organ failure, and septic shock. Others were cancer patients at the end of life. “By the time they got to us, they were pretty sick. We saw a lot of death on the floor.”

But death by COVID was different, especially at the beginning of the pandemic when so little was known about the disease.

The first of Gluck’s patients to die of COVID was a man whose blood pressure had dropped so low that it wasn’t “compatible with life,” she said. Gluck conferred with several colleagues, including the attending physician. Having tried all possible medications and interventions, they agreed there was nothing else they could do.

“We knew this horrible disease had won, but it was hard to accept,” she said. “We don’t take defeat lightly.”

Earlier in the night, Gluck had spent three hours with the patient. One of the medical fellows said she would stay with him so he wouldn’t die alone. Without another patient to check on at the end of her shift, Gluck wrote up her notes and headed home. “It was weird and unsettling leaving that night, knowing that we had done everything possible and he would still die.”

As the initial shock of treating COVID patients subsided, Gluck said, it was surprising how quickly her work began to seem normal. “But it doesn’t take away the sadness.”

She said one day she might be surprised how she pushed herself emotionally and physically during the pandemic. It’s more likely she won’t. “This is what I do as a nurse. This is my job.”

Taylor Campbell watched as her new patient — a 67-year-old woman — was wheeled into a room on the COVID unit of an East Harlem hospital. Sedated and on a ventilator, the woman initially presented with a cough, fever, and shortness of breath. When Campbell heard that the woman’s daughter had died a few days earlier from the coronavirus, she thought, “Oh no, we can’t have this happen again.”

For the next 15 days, working from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m., she took care of the woman, bathing her and talking about the boyfriend and three dogs she had left behind in Rhode Island to take a temporary assignment at the hospital.

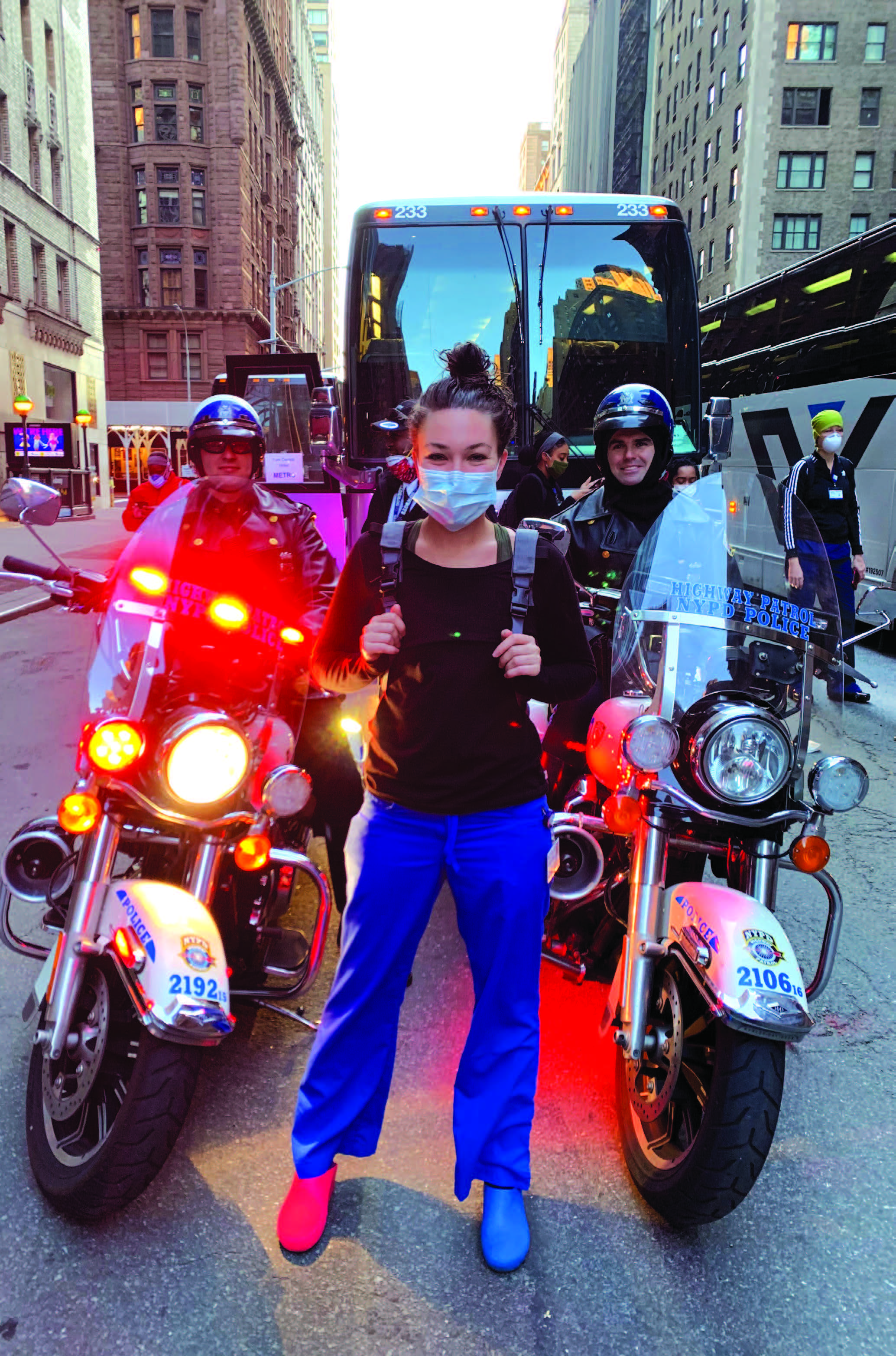

Campbell, B.S.N. 2015, was working as a per diem nurse in the emergency department of a hospital near her home in South Kingstown. She had just finished the coursework required to become a nurse practitioner, but the licensing exam had been cancelled, so she and a friend decided to sign up for a three-week nursing assignment in New York City. Campbell tried for hours to get through to the agency that was hiring nurses and other health-care workers to beef up staffing in hospitals around the country. When she finally got through to someone, they asked for only two pieces of information: her area of expertise and her license number to prove that she was a registered nurse.

Her parents bought her groceries and less than 24 hours after taking the temporary assignment, she was in New York City. After checking into her hotel, she walked from Times Square to Pier 90 in Manhattan, where the USNS Comfort hospital ship was docked. With New York under a stay-athome order, most of the streets were empty.

Taking pictures as she walked, Campbell remembered her father’s stories about New York City in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Then an officer with the Providence, R.I., police department, he volunteered to go to Manhattan to help with security near the World Trade Center. Campbell was in third grade at the time. When he returned, he showed her photos of deserted streets in Times Square, saying that she’d never see such images again in her lifetime.

The next morning she was up at 6:15 to catch a shuttle to NYC Health + Hospitals/Metropolitan, located in a predominantly Hispanic community. That night, she got back to the hotel around 8:30, put her dirty scrubs and shoes in separate bags, had a bite to eat, and went to bed. Every day, for the next three weeks, her routine was the same. Her days were often chaotic and frenzied. She described the hospital as “a war zone.”

The Metropolitan staff was exhausted. At first, Campbell didn’t know where supplies were kept. She wasn’t familiar with the hospital’s procedures. She spent several days helping to convert an unused floor into a makeshift ICU and then she was assigned to care for the woman whose daughter had died.

Campbell said she was “blown away” when she looked at the woman’s chest X-ray. Healthy lungs are black and outlined in white on an X-ray. The heart appears as a silhouette. On the patient’s X-ray, her lungs were white, with the ground-glass opacity characteristic of COVID. The appearance of her lungs indicated they were swollen and inflamed, making it difficult for her to get enough oxygen even with a ventilator.

In the morning, Campbell would open the shades in the woman’s room and, throughout the day, tell her what she was doing, whether it was taking her temperature or giving her medication. Her patient couldn’t talk, but she could hear.

“She couldn’t take care of herself,” said Campbell. “I was the mom and she was kind of my baby. She became my family.”

Meanwhile, elsewhere on the unit some COVID patients were suffering from kidney failure. Initially there weren’t enough dialysis machines or nurses trained to conduct dialysis. About halfway through Campbell’s assignment, the hospital started training. But, for some patients, it was too late. They had already passed away.

While she was in New York City, Campbell posted Facebook messages about her experience to keep her family and friends in the loop. In mid-April, a reporter with the Providence Journal interviewed her. When the article appeared, national news outlets saw it and her story went viral. Interviews with Campbell ran on MSNBC and ABC News Prime. Her Facebook page was flooded with messages from people around the world.

In the ABC interview, Campbell described the moment when her patient was taken off the ventilator. The tube in her throat was removed and a BiPAP machine was placed on her face, allowing pressurized air to flow into her lungs. “She looked right at me and said, ‘I love you’,” recalled Campbell.

Starting to tear up, Campbell said she wanted family members of patients to know that “we’re taking really good care of [their loved ones] and we’re treating them like they are our family.” While caring for the woman, Campbell said she often sat on the side of her bed and held her hand. Campbell said that personal interaction was significant for her as well.

“There wasn’t anyone I could hug. She and I were there for each other.”

The next day she returned to her home in South Kingstown, where her parents and family gave her a boisterous, socially distanced welcome with a blaring horn and a clanking cowbell. She spent the next couple of days catching up on sleep and walking her dogs. One night, Campbell suddenly sat up in bed, but she was still asleep. She described the episode as “a stress nightmare” that used to occur when she worked in the emergency department.

On Facebook and in the news, some people praised Campbell as a hero who had volunteered her time in New York City. She bristled at the description.

“I don’t feel like a hero,” said Campbell, who now is a licensed family nurse practitioner. “A lot of other nurses were dealing with [COVID] before I got to New York. They’re still there. They’re the heroes.”