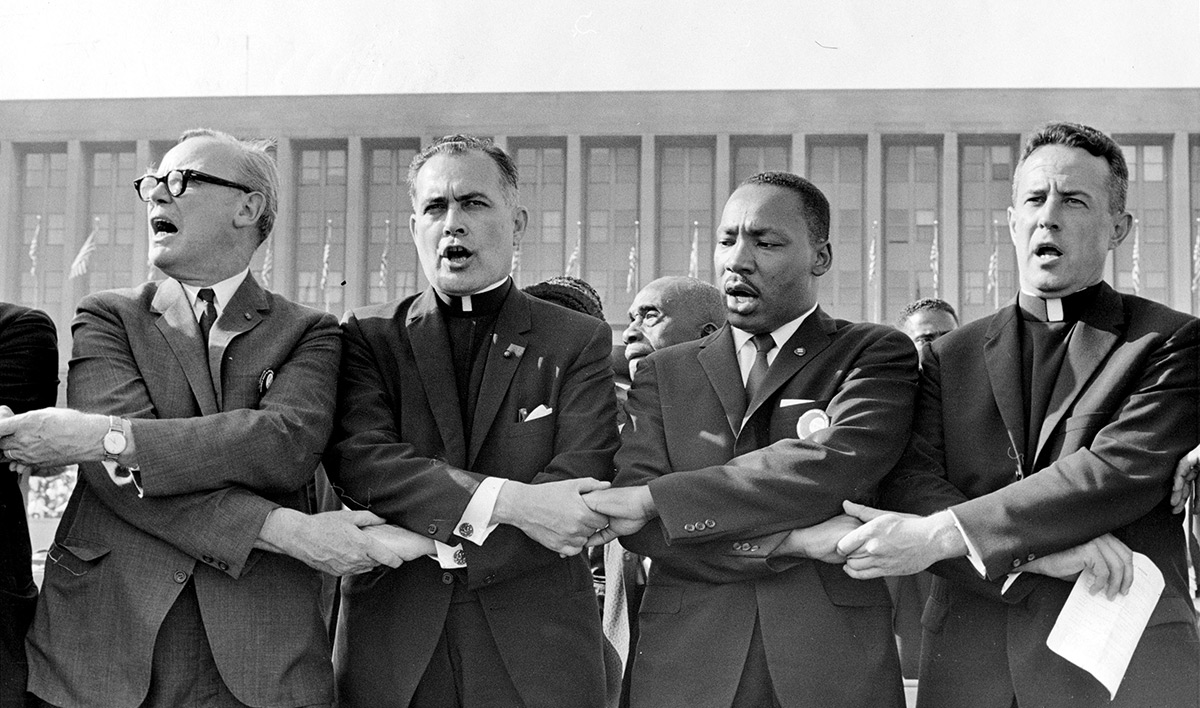

Catholic University alumnus Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C. (second from left), former president of the University of Notre Dame, joins Martin Luther King Jr. in singing “We Shall Overcome” during a rally in support of the Civil Rights Act at Soldier Field in Chicago, 1964. (University of Notre Dame).

By Kevin M. Burke

2020 presented Americans with scenes of racial turmoil — some of the most controversial occurring in Washington, D.C. — reminiscent of the turbulent days of the 1950s and ’60s civil rights movement. The question for the Catholic community now, as then, is: Are we equal to the moment?

Video clips and news stories largely describe only the elements of something: the who, what, when, and where. Sometimes they get after the “why,” but generally still struggle to convey the feeling of those moments and emotions on the ground — the way a YouTube video of an earthquake in Japan can show you what a 7.1 temblor looks like, even suggest how frightening that situation must be, but can never transmit the sense of the earth shifting beneath your feet.

That’s how this story began, with a sense of something.

University Chaplain and Director of Campus Ministry Rev. Jude DeAngelo felt it, like the wave of heat and humidity that overtakes Metrorail riders ascending from the cool of Farragut North station in downtown D.C. on a summer day. In early June, Father Jude and a contingent of CatholicU students, faculty, and staff rode up that escalator en route to a Catholic community prayer service at Lafayette Square near the White House.

Not in Lafayette Square, which was intermittently closed to the public throughout the summer to allow the National Park Service “to assess damage and make repairs to statues and other park resources” after protests in the immediate aftermath of George Floyd’s death at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer in May. Although on this day, the most recent tumult at Pennsylvania Avenue and 16th Street N.W. was the preceding week’s tear-gassing and forcible eviction by federal officers of mostly peaceful demonstrators from the square in order to facilitate a photo opportunity featuring President Donald Trump and a Bible in front of nearby St. John’s Episcopal Church — an episode widely criticized by religious leaders of all denominations.

Not in Lafayette Square, which was intermittently closed to the public throughout the summer to allow the National Park Service “to assess damage and make repairs to statues and other park resources” after protests in the immediate aftermath of George Floyd’s death at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer in May. Although on this day, the most recent tumult at Pennsylvania Avenue and 16th Street N.W. was the preceding week’s tear-gassing and forcible eviction by federal officers of mostly peaceful demonstrators from the square in order to facilitate a photo opportunity featuring President Donald Trump and a Bible in front of nearby St. John’s Episcopal Church — an episode widely criticized by religious leaders of all denominations.

“I was jolted,” says Father Jude, “because he didn’t seem to pray when he got to St. John’s, and to me that would have been the perfect opportunity. It could have been a moment for our president to bring people into that moment for prayer as a layman, as a civil leader. So I just didn’t want to see this continue to be only a political moment at our churches, whether at an Episcopal church or our Catholic shrine. The visual of it was not good, and that’s why I went down [to the prayer service].”

Members of the Washington, D.C., Catholic community demonstrate in Black Lives Matter Plaza next to Lafayette Square and across from the White House, days after peaceful protestors were forced from the square by federal officers in order to facilitate a presidential photo op at nearby St. John’s Episcopal Church. (Bob Roller/Catholic News Service)

Organized by Josephite Father Cornelius Ejiogu, a local pastor, and endorsed and promoted by Washington Archbishop, now Cardinal Wilton Gregory, the prayer service offered a counternarrative that Father Jude feels is vital not only in response to those who commandeer sacred spaces for partisan politics, but also to others who suggest that Black Lives Matter — as a rallying cry for social change — somehow conflicts with Catholic faith.

“We in the Catholic Church have not talked about it, about racism, prejudice, enough,” Father Jude says. “I know that Black Lives Matter also has been politicized with things that are contrary to our Catholic faith. But, I think for the majority of people, as a banner for justice it represents something that is important right now in terms of race relations, and the Catholic Church needs to be in the forefront of that.”

University Chaplain and Director of Campus Ministry Father Jude DeAngelo, O.F.M. Conv., protests through prayer while President Trump’s motorcade passes by on the way to the St. John Paul II Shrine next to campus on June 2. “I always pray for peace,” says Father Jude. “I pray for peace in our cities and that we would move away from thinking that everything has a political solution to it.”

It could be the name of a 1990s-era all-girl rock band: Shannen Williams and the Subversive Nuns. Instead it’s the title of an upcoming book, Subversive Habits: Black Catholic Nuns in the Long African American Freedom Struggle, by Shannen Dee Williams, the Albert Lepage Assistant Professor of History at Villanova University and an emerging voice on the history of Catholicism, slavery, education, civil rights, and Black power.

In her study, which will offer the first historical survey of Black Catholic sisters in the United States, Williams unearths their hidden history in the fight to dismantle racial and gender barriers in the U.S., within both the Catholic Church and society at large. Before the reforms of the Second Vatican Council, these contests would be waged primarily in the nation’s Catholic convents, classrooms, and hospitals.

Forgotten, Williams says, is that long before the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education outlawed the concept of “separate but equal” in the administration of American public schools, Black sisters had fought and won battles to desegregate historically white Catholic colleges and universities and, later, congregations of women and those orders’ respective institutions across the country. She argues the nation’s Black sisterhoods, established in response to longstanding anti-Black admission policies of white congregations, laid the foundation upon which Black Catholic communities challenged segregation and discrimination within the Church and wider society.

Although they were careful not to overtly challenge the axiomatic white supremacy they encountered, Williams says the sisters adopted a “very conscious approach” — opening high-achieving schools for Black Catholic youth, quietly working to desegregate Catholic higher education — “to equip their students with the tools and worldview to fully dismantle racial segregation when the time came.”

By creating those Black Catholic institutions, sustaining them, making them the best possible, these Black women were in their own right freedom fighters, says Williams, and it is time to see them and take inspiration from them as such.

“They are absolutely insurrectionary, they are absolutely subversive,” adds Williams, who is scheduled to deliver an invited lecture at Catholic University during the spring semester. “They refused to accept Jim Crow as moral in any way, but they also took the long view in the fight against white supremacy. They’re saying, ‘We’re going to get there at some point. We are on this journey and we have a critical role to play as educators of Black youth.’ The marching in the streets for voting rights, open housing, and an end to police brutality, that came later.”

The first class of postulants of what was then known as the Sisters of Mary Colored Community, St. Louis, 1946. The nation’s Black sisterhoods, formed in response to longstanding anti-Black admission policies of white congregations, set the stage for Black Catholic communities to later challenge segregation and discrimination in American society more broadly, says Villanova University history professor Shannen Williams. (American Catholic History Research Center/Catholic University)

Especially in the late 1960s and early ’70s, when ethnic strife, church divestment, urban decline, inflation, and other forces put pressure on many Catholic schools in predominantly Black and inner-city communities to close, Williams says Black sisters rallied to preserve the Black Catholic educational system. These activist-oriented nuns “understood that their institutions were a part of the Black freedom struggle, that quality education was — as it remains today — absolutely essential to any struggle for justice and equity.”

A suggestion that someone wanting to write an activist handbook about stirring up what the late Congressman John Lewis called “good trouble” could get a good start by going through the center’s records is greeted as nothing new by Maria Mazzenga, Ph.D. 2000, curator of the American Catholic History Collections within Special Collections in Mullen Library. A significant portion of the evidence Professor Williams found for championing the achievements of Black Catholic nuns she located in the collections at CatholicU, where she spent several months as the recipient of a University-sponsored Dorothy Mohler Research Grant.

The disparate geographies and practices among religious communities regarding the privacy or confidentiality of records can make the Catholic historian’s job more challenging, explains Williams, making those concentrations of resources that do exist — such as those held by the University in Aquinas Hall — highly valuable.

“Having access to those records allowed me to truly understand the context in which these sisters were operating,” she says. “I was able to reconstruct a lot of that history, to recover some of those lost chapters, using the materials at Catholic University.”

Alongside Williams’ subversive nuns, the University’s archives contain the notes of Father George Gilmary Higgins (1916–2002), the labor activist known as the “labor priest” for his unionization work with Cesar Chavez; Bishop Francis J. Haas (1889–1953), former chairman of the President’s Committee on Fair Employment Practice, who as a mediator for the National Labor Board, helped settle the Minneapolis Teamsters strike in 1934; Father John Ryan, S.T.L. 1900, S.T.D. 1906 (1869–1945), the initial proponent of a national minimum wage; and Church historian Father Cyprian Davis, S.T.L. ’57 (1930–2015), author of the definitive The History of Black Catholics in the United States (1990).

“I’d estimate 50 percent of our researchers are interested in some sort of social justice issue,” says Mazzenga. Though the materials documenting major movements like the National Catholic Conference on Interracial Justice and prominent figures such as Dorothy Day command significant attention, she urges that the contributions of lesser-known activists — including Catholic University’s own Monsignor Paul Hanly Furfey, Ph.D. 1926, and Martha Euphemia Haynes, Ph.D. 1943 — should not be overlooked.

Furfey, the former head of the University’s sociology department, co-founded three settlement houses in impoverished neighborhoods in D.C. while co-directing the Juvenile Delinquency Evaluation Project (JDEP) in New York City. Haynes — known mostly for her distinction as the first African American woman to earn a Ph.D. in mathematics — went on to serve many years as a member of the D.C. school board. She was a strident opponent of the practice of tracking or grouping children together according to their talents in the classroom, Mazzenga says, because she felt it directed more minority students into vocational programs.

“She thought it kept African American students from actually exploring college-related topics before they went on to college,” says Mazzenga, also an adjunct instructor in the departments of History and Library and Information Science. “She was very integral to the board’s activities on this into the 1960s and beyond, so in that way had a great influence on the educational opportunities of many of those students.”

Ajani Gibson, B.A. 2015, is a young, Black seminarian living in Louisiana, who says the inspiration for his vocation is a white man from Caribou, Maine. Father Michael Jacques’ sudden death in 2013 at the age of 69 sent shock waves through the New Orleans neighborhood of Treme he served for more than 20 years, and where Gibson grew up.

Even in his youth, Gibson says, he was impressed that Jacques would “come into the heart of the Black community in New Orleans to … see for himself the needs in the community for education and healthcare and mental health services.

“To see him and his fight, saying, ‘Black people need to have a place at the table.’ That, particularly, inspired and contributed to my own vocation.”

Gibson serves today as a transitional deacon, the last step before his ordination, at St. Louis Cathedral in New Orleans. His home parish is St. Peter Claver. Named for the Spanish Jesuit priest who through his life’s work and evangelization became known as the patron saint of slaves, the church celebrated its centennial in 2020 and continues to promote the rich culture and traditions of Black Catholics in the city, the Bayou State, and the greater South, says Gibson. His own activism — through his writing, Internet videos, and social media posts, as well as deep and sometimes difficult personal conversations “in rooms where other [Black] people can’t go” — focuses on bringing more people of color into vocation.

“If we don’t, a necessary voice, a necessary gift to the Church will be lost,” Gibson says, with a quick reminder that St. Augustine was a Black man from Numidia in North Africa. “So the roots and contributions of people of color aren’t just as far back as the ’50s and ’60s. They go back to the beginning.”

Although the number of Black Catholics in America has grown tenfold since World War II — from fewer than 300,000 to some 3 million today, according to the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops — there is nothing to indicate proportional growth in the number of Black priests and bishops, which today number just 250 and eight, respectively.

Changing those data points significantly means “making my experience relatable to those who may not understand or may not even agree or maybe even deny some of the realities that I have to face as a Black man in America, but also as a Black man in the Church,” says Gibson. “We need to reconfigure how we image the Church, how we image sanctity, the lens through which we promote theological thought … and that’s a lot of work to do.”

For many, the passing in July of civil rights icon and longtime Georgia Rep. John Lewis brought back memories of the 1960s civil rights movement. A well-known photograph from the era depicts Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., S.T.L. 1944, S.T.D. 1945 — former president of Notre Dame — demonstrating arm-in-arm with Martin Luther King Jr. in support of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 Chicago.

First appointed by President Dwight Eisenhower, Hesburgh served 15 years as a member of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission, including three as its chair (1969–72), before he was dismissed by President Richard Nixon over his objections to the administration’s slowdown policy on school desegregation.

Civil rights, said Father Ted (the affectionate moniker applied to him by students and admirers alike throughout his public life), “were not created, but only recognized and formulated” by the instruments of government. They “are important corollaries of the great proposition … that every human person is a res sacra, a sacred reality, and as such entitled to the opportunity of fulfilling those great human potentials with which God has endowed every man.”

President Jimmy Carter would later call on Hesburgh to serve on the U.S. Select Commission on Immigration and Refugee Policy in 1979. The picture of Father Ted and Dr. King is now part of the permanent collection of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Portrait Gallery, in many ways representing not just a moment, but also for some, a movement frozen in time.

Over the nearly six decades since an unknown photographer captured the Catholic priest and Baptist preacher together onstage, “the Church in its own institutions and kind of in its own day-in-and-day-out processes has not been as aware and as proactive in regards to being anti-racist as it could be and as it should be,” believes Stephen Schneck, who recently retired from his roles as associate professor of politics and director of the University’s Institute for Policy Research and Catholic Studies. He continues more than 30 years of Catholic activism today as executive director of the Franciscan Action Network, collaborating with some 50 Franciscan communities across the country to transform public policy related to peacemaking, the environment, poverty, and human rights.

While acknowledging there have been a number of “flare ups” of awareness about racial justice over the last 60 years — the Harlem-based Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture records more than 100 significant incidents of racial unrest in the U.S. since 1970 — “they’ve all tended to be kind of moments of consciousness awakening within the ‘usual suspects’” of activists and other people who have worked on social justice issues, Schneck says. “And, of course, among people who have been directly impacted by racial injustice.”

But, none of those events seems to have had the kind of broad reach in our society and culture that Schneck feels is happening now. He sees at least “a chance of kind of a big step within our country and our Church in the direction of racial justice.

“What’s different now, I think, is that white teenagers are in the crowd, soccer moms are in the crowd, young children, cab drivers, school teachers, doctors and nurses are in the crowd… You know, it’s not just a collection of a few celebrities and activists that are on the front lines, it’s the whole country. So, I feel it’s that breadth is what’s so distinctive about this time. And that there’s a real authenticity about this. It really feels genuinely authentic in that it’s coming up from below and this is a spontaneous arising.”

Here’s the thing about earthquakes: even in the most energetic and disruptive, the converging or shearing tectonic plates move only a few feet. But move they do, and in the context of geologic time the results are dramatic. Today, Los Angeles and San Francisco are located roughly 340 miles apart along the eastern edge of the so-called Pacific Rim of Fire. Though in 16 million years, give or take, would-be Angelenos will be able to wave to their new southern neighbors as L.A. continues its inexorable slide past the Golden Gate.

In Catholicism, the rough equivalent of this idea is the time-worn expression that the Catholic Church thinks in terms of centuries. A dilemma arises, however, when trying to reconcile this idea with Dr. King’s “fierce urgency of now.” Schneck suggests some resolution may be found by looking at society’s progress on civil rights, like plate tectonics, as a succession of “now” moments that gradually advance humankind’s perception and sensitivity about civil rights.

Gibson’s view is more personal and pastoral. He tells the story of New Orleans Auxiliary Bishop Harold Perry (1916–1991), the first African American to serve as an American Catholic bishop in the 20th century. Despite conferring directly with President John F. Kennedy in 1963 on peaceful desegregation, “a lot of people criticized Bishop Perry because they wanted him to be the Catholic MLK,” says Gibson.

“They wanted him to shake things up. And he would say, ‘I have my own ways of pushing the system. But I have to be attentive of those who are coming behind me.’ Because if he’s the first radical, then there would not have been an Archbishop [Eugene Antonio] Marino (the first African American archbishop in the U.S.) or Archbishop (James Patterson) Lyke (Cleveland; Atlanta). [Cardinal] Wilton Gregory would not be the archbishop of Washington in 2020 if Bishop Perry was radical in the way that people wanted him to be.”

Part of the illustrious group of preachers inducted into the Martin Luther King Jr. Board of Preachers at Morehouse College and a recipient of the Cardinal Bernardin Award from the Catholic Common Ground Initiative for his work to foster unity in the Church, Cardinal Gregory assumed his latest role as Washington archbishop and University chancellor in May 2019. Like Bishop Perry, he has also received criticism — including from within the Church — though in his case for strongly criticizing President Trump’s photo ops at St. John’s Episcopal Church and the Saint John Paul II Shrine near campus in June.

“On one level, it is disappointing that we are still grappling with some of the same issues that Dr. King and his colleagues in the civil rights movement struggled with. It is frustrating that we’re still trying to bring a greater sense of harmony and unity and racial justice to this nation,” says the nation’s first African American cardinal (see page 10). “But, I’m just grateful that we still have people who are willing to carry on that struggle.

“You know, Dr. King often used the phrase, ‘How long? Not long.’ So, even in his own work and in his statements, he kind of prepared us for the long haul, the struggle that is still going on. And in this particular moment, when I see so many young people energized, committed … I take great heart at that. That there’s another generation that will carry on.”